Nurse Perspectives Regarding the Meaningfulness of Oncology Nursing Practice

Background: Recruiting, retaining, and training oncology nurses is challenging given the stress levels associated with a field with constantly evolving treatments and a need for expertise in death and dying.

Objectives: This research was conducted to assess what is unique about oncology nursing, to identify what motivates oncology nurses to continue working in the specialty, and to determine what sustains them in daily practice.

Methods: A phenomenologic approach was used to analyze data.

Findings: Nurses identified three main themes: the importance of vulnerability and thankfulness in patients, the feeling of spirituality associated with oncology practice, and the value of being in the moment and recognizing priorities as meaningful aspects of oncology nursing.

Jump to a section

Stress levels in oncology nursing are high because nurses work with patients and families over an extended time period, a significant number of patients pass away, and oncology practice requires that nurses maintain up-to-date skills and knowledge in an environment that is constantly changing (Ekedahl & Wengström, 2010). A number of authors have discussed that oncology nurses are motivated by sustaining relationships that they develop with patients and their families (Berterö, 1999; Dowling, 2008). To develop effective training programs, having a complete understanding of what prompts experienced nurses to continue working in oncology and recognizing how oncology nursing differs from other specialty areas are vital.

Background

From 1992–1994, the Oncology Nursing Society (ONS) Life Cycle Task Force published a series of articles from a multisite study of the meaning of oncology nursing, which focused on factors that affect recruitment and retention of oncology nurses. A major theme of the Life Cycle Task Force was that working in oncology requires an ability to “be there” with patients and their families, the capacity to focus on patients’ needs, and the skill to develop a sustaining relationship with patients (Cohen & Sarter, 1992; McDonnell & Ferrell, 1992; Steeves, Cohen & Wise, 1994). Bakker et al. (2010) formed focus groups across Canada to determine what factors influenced recruitment and retention in oncology nursing. They reported that the following factors are important: recognizing oncology as a specialty, understanding that life experience is an important factor in oncology nursing, and acknowledging that expressions of gratitude from patients are motivating. Cohen, Ferrell, Vrabel, Visovsky, and Schaefer (2010) documented that, although major changes have occurred in health care, the experiences that motivate oncology nurses have remained fairly consistent over time. However, given technologic discoveries and practice changes (Adelson et al., 2014; Caligtan & Dykes, 2011; Carney, 2014), whether the sustaining nature of the nurse-patient relationship remains the primary motivator of nurses to work in oncology is unknown.

Methods

A qualitative, phenomenologic investigation (Benner, 1994) was conducted with members of a Northern California ONS chapter to determine what is unique, meaningful, and motivating in their practice. A one-hour audio-recorded interview was scheduled following a regular meeting of the ONS chapter. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of California, Davis.

Participants and Interview Prompts

Eight nurses volunteered to be interviewed for this purposive sample. Four participating nurses had a bachelor’s degree in nursing, and four had a master’s degree. Two nurses were aged 31–40 years, one nurse was aged 41–50 years, and five nurses were aged 61 years or older. Two participating nurses were African American, and six nurses were Caucasian; all were female. One nurse had worked less than three years in oncology, and seven nurses had been oncology nurses for more than three years. One nurse worked on a mixed medical-surgical unit, and seven worked in oncology specialty units. Seven nurses had previous medical-surgical experience before becoming oncology nurses, and one nurse began her career as an oncology nurse. Nurses were asked to reflect on the following questions.

• How is being an oncology nurse different than being a medical-surgical nurse?

• What motivates you to continue working as an oncology nurse?

The first author conducted the interview and asked participants to elaborate on and clarify comments as needed. The interview ended when the nurses had nothing new to add and redundant themes appeared in the material being shared.

Data Analysis

The interview was transcribed verbatim and checked for accuracy by listening to the audio recording several times. Two researchers reviewed the transcripts and identified repetitive themes. A list of meanings was compiled and clustered to determine if the themes overlapped and accurately reflected the essence of the nurses’ experiences (Hycner, 1985). Each researcher reread the entire interview as they checked for “incongruities, puzzles, and unifying repeated concerns” (Benner, 1994, p. 113). When a finding was identified that both researchers did not agree on, they returned to the original transcript and reexamined the meanings that were presented by the nurses. Consensus regarding findings was achieved using this approach. Numerous quotes are included in this article so that readers are able to participate in consensual validation of the data and assess whether the interpretations match nurses’ experiences (Madison, 1988).

Findings

The nurses identified three main themes: "the importance of vulnerability and thankfulness in patients," "the feeling of spirituality and grace associated with oncology practice," and "the value of being in the moment and recognizing priorities as meaningful aspects of oncology nursing."

Vulnerability and Thankfulness in Patients

Nurses stressed that they were motivated to provide excellent care to patients with cancer by how thankful these patients are.

I always felt I was an oncology nurse. When I got my first job right out of school, I felt like, “This is home.” It was the instant connections I made with oncology patients that were different than what I had felt with medical-surgical patients. Even early on, I felt like I had an ability to meet oncology patients where they were at compared to working with medical-surgical patients where I felt robotic. Oncology patients respond like the nurse is a gift to them, and I always felt like the patients were a gift to me as well. I got a job as an aide the summer before I graduated, and oncology patients had just begun to be merged into my unit. One day, the charge nurse told me I could work on the medical-surgical side of the unit. I went home and felt sad. That’s when I decided I would be an oncology nurse. It was that the oncology patients were vulnerable. The medical-surgical patients didn’t need me in the same way. I knew how to talk to someone in trouble, and that felt worthwhile.

Another nurse agreed that the appreciation and thankful attitude that patients with cancer exhibit, as well as the ability to make a difference in someone’s life, motivated her.

Oncology patients and their families have a deep appreciation for your time and whatever information you give them. I don’t see that with medical-surgical patients. Medical-surgical patients have a “give me more” attitude. For oncology patients, it’s about being able to be there at 10 pm at night when they need someone to listen to them. It’s a different feeling. Oncology patients appreciate everything that is done by staff. There’s a different sort of thankfulness in oncology. Patients are grateful when they get to see their granddaughter graduate or their great-grandbaby born. There’s a feeling of satisfaction as an oncology nurse knowing you make a difference in someone’s life.

A third nurse commented that the vulnerability she experiences working with patients with cancer taught her to be a better person, to be thankful, and to always learn from her practice.

In my career, what I was looking for was a way to connect and follow through with someone’s journey. It’s the priority thing—the enjoy-today, live-the-moment, get-the-most-you-can-out-of-today attitude. The memories of a young girl talking to a stuffed toy like it was her brother who had passed away stay with you. My memories have gotten me through a lot. Oncology patients have taught me how to deal with life—how to appreciate situations and be thankful, how to be a more caring person. You learn what’s most important in life by dealing with patients who are dying. Oncology patients are so vulnerable; they pull the best of me out.

Spirituality and Grace

One nurse described how being present with a patient, really focusing on the patient, and experiencing the sense of spirituality associated with her practice helped to motivate her.

I start each day with a prayer: “God, let me be your eyes and ears for today.” That reminds me it’s not about me. It also helps me recognize that success is helping someone find peace or be more comfortable. It’s about being in the moment with someone.

Another nurse reflected on how the sense of grace and caring she found in oncology nursing motivated and sustained her.

One little guy I worked with died, and I wrote a note to his family about what I had gained by working with him. His grandmother came back and said, “Thank you.” He was only 2, and she didn’t think anyone would remember him. It’s those small ways of touching lives and helping some-one get to where they need to be that matter—knowing you can’t change things but you can help get somewhere with grace, with love, with support.

A third nurse commented that oncology is a compassion, a calling, and a passion that helps you change others' lives and your own life as well.

We all have different personalities, so each person who interacts with a patient does something different to make the person’s life better. One patient told me, “You don’t realize the small things you do so naturally can change a day and shift a mood.” I saw this woman eight hours every Friday. She said, “I wish nurses understood how the little pat on the shoulder, the joke, the smile can make your day better.” Oncology is a compassion, a passion, a calling, a vocation—not a job. Oncology is a joy that enlarges your life and allows you to live other lives and to grow spiritually as a person.

Being in the Moment

One nurse highlighted the importance of being truly present in the moment, identifying what is most critical in life, and opening your heart to another person—attitudes she learned by interacting with patients with cancer.

I started as a psychiatric nurse [and] then worked in home health before coming to oncology. In oncology, how you relate to patients is more long-term and more intense. You have to be in the moment. What you are dealing with is so intense, you don’t have time to worry about your mortgage or grocery shopping. You have to focus on what is most human about your patients. Oncology teaches you about setting priorities and what is important. One of my patients told me, “You were chosen to do this.” I thought to myself, “I don’t believe that,” but I thought about it again, and there is a specific feeling associated with being comfortable in your role as an oncology nurse. Oncology requires you to open your heart each day, acknowledging you can get hurt.

A second nurse said that patients with cancer have helped her recognize the important priorities in life.

You need to take care of yourself, and that has to do with boundaries, but boundaries in oncology nursing are a bit different. There is more of a tendency to identify with and empathize with oncology patients. I can’t think of anyone I know who hasn’t been touched by cancer, whether it is at work or at home. You also need to play, laugh, read, live your life, and get some space. Oncology patients have taught me to identify what’s important—what’s the “you” in all that’s around you. I do something for myself each day, come rain or shine. I do that whether the house is burning down or not.

Another nurse reiterated how important being in the moment and being truly present can be.

I felt inadequate when I was a new nurse. Another nurse said to me, “Whatever it is you are doing is more than what this person would have had without you.” That’s a comforting thought. It’s really about being in the moment with someone and knowing that is enough.

Knowledge Translation

A unique finding of the current study is the degree to which the vulnerability and nondemanding nature of patients with cancer enable nurses to truly focus on the patients and be present in the moment with them. As Noddings, a caring theorist, reflected, being truly engrossed with the one being cared for is characterized by a “move away from self” (Noddings, 1984, p. 16). This vulnerability that patients with cancer exhibit may contribute to the feelings of grace and spirituality that oncology nurses describe as an important aspect of their practice.

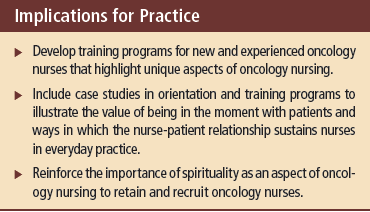

By highlighting the unique nature and meaning that other nurses have found within oncology practice, new nurses can be motivated to select the specialty and to appreciate the significance of working with patients with cancer. Reiterating themes that nurses have described as being critical aspects of oncology nursing also may help retain experienced nurses. More effective continuing education programs can be developed if the perspectives of experienced nurses are elicited and shared by publishing rich, descriptive data.

Implications for Nursing

To design effective training programs for oncology nurses and to recruit and retain nurses within a stressful profession, what motivates and sustains nurses must be recognized. Having nurses share motivating experiences is a good way to emphasize the caring art of oncology nursing, to foster the productivity of working oncology nurses, to motivate new nurses, and to promote the specialty. Vioral (2011) emphasized that linking students with nurses who belong to professional organizations, such as ONS, is a good way to introduce new nurses to specialty careers. Experienced nurses should share how they became oncology nurses and discuss reasons why they continue to work in the specialty. Oncology nurses also must participate in career fairs and join with human resource personnel to convey a positive image of cancer care to maximize recruitment efforts. Using highly motivated, experienced oncology nurses to co-teach portions of undergraduate and graduate curriculum and to increase the amount of oncology content in educational programs also is important (Bakker et al., 2010). Training programs for oncology nurses should include content focused on how to provide spiritual care to patients and content that highlights the importance of a sense of spirituality in retaining oncology nurses.

Additional, larger studies are needed to examine factors that make oncology nursing unique, to explore ways to promote retention and recruitment, to determine how the length of experience in oncology nursing influences nurse perceptions, and to compare responses of oncology nurses with those of other experienced nurses. Additional research also is needed to determine what factors interfere with student nurses considering a career in oncology nursing.

Limitations

Limitations of the current study include that most (five of eight) of the participating nurses were aged 61 years or older and all were women. As is common for a qualitative study, the sample size of eight was small and homogeneous. Whether younger oncology nurses and male oncology nurses are motivated and sustained by similar experiences is something that requires additional studies.

Conclusions

Oncology nurses who participated in the study stressed that they recognized the qualities of vulnerability and thankfulness typically seen in patients with cancer, grew as a result of feelings of spirituality and grace within their practice, and valued the experience of being in the moment and recognizing life’s priorities as a result of their work in oncology.

According to van Rooyen, le Roux, and Kotzé (2008), a dearth of research still exists regarding the experience of oncology nurses, including what motivates them, what is unique about their practice, and what sustains them. Van Rooyen et al. (2008) reported a number of findings similar to the findings from the current study. They found that oncology nurses: (a) are deeply aware of the need to be in the moment and live each day in a meaningful manner, (b) experience their interactions with patients as having a spiritual quality, (c) recognize that their relationships with patients with cancer are different than their relationships with any other type of patient, (d) appreciate the thankfulness that patients with cancer express, and (e) note that patients with cancer ask for less than other types of patients, regardless of their need. Bakker et al. (2010) also reported that an expression of gratitude from patients is a major factor that promotes retention of oncology nurses. Ekedahl and Wengström (2010) commented that oncology nurses value the relationships they have with patients with cancer, appreciate the reminders about the importance of living each and every moment, and welcome ways in which their work with patients contributes to their own personal growth as a nurse and a human being.

References

Adelson, K.B., Qui, Y.C., Evangelista, M., Spencer-Cisek, P., Whipple, C., & Holcombe, R.F. (2014). Implementation of electronic chemotherapy ordering: An opportunity to improve evidence-based oncology care. Journal of Oncology Practice, 10, e113–e119. doi:10.1200/JOP.2013.001184

Bakker, D., Butler, L., Fitch, M., Green, E., Olson, K., & Cummings, G. (2010). Canadian cancer nurses’ views on recruitment and retention. Journal of Nursing Management, 18, 205–214.

Benner, P. (1994). Interpretive phenomenology: Embodiment, caring, and ethics in health and illness. London, UK: Sage.

Berterö, C. (1999). Caring for and about cancer patients: Identifying the meaning of the phenomenon “caring” through narratives. Cancer Nursing, 22, 414–420. doi:10.1097/00002820-199912000-00003

Caligtan, C.A., & Dykes, P.C. (2011). Electronic health records and personal health records. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 27, 218–228. doi:10.1016/j.soncn.2011.04.007

Carney, P.H. (2014). Information technology and precision medicine. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 30, 124–129. doi:10.1016/j.soncn.2014.03.006

Cohen, M.Z., Ferrell, B.R., Vrabel, M., Visovsky, C., & Schaefer, B. (2010). What does it mean to be an oncology nurse? Reexamining the life cycle concepts. Oncology Nursing Forum, 37, 561–570. doi:10.1188/10.ONF.561-570

Cohen, M.Z., & Sarter, B. (1992). Love and work: Oncology nurses’ view of the meaning of their work. Oncology Nursing Forum, 19, 1481–1486.

Dowling, M. (2008). The meaning of nurse-patient intimacy in oncology care settings: From the nurse and patient perspective. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 12, 319–328. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2008.04.006

Ekedahl, M.A., & Wengström, Y. (2010). Caritas, spirituality and religiosity in nurses’ coping. European Journal of Cancer Care, 19, 530–537. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01089.x

Hycner, R.H. (1985). Some guidelines for the phenomenological analysis of interview data. Human Studies, 8, 279–303.

Madison, G.B. (1988). The hermeneutics of postmodernity: Figures and themes. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

McDonnell, K., & Ferrell, B.R. (1992). Oncology Nursing Society Life Cycle Task Force report: The life cycle of the oncology nurse. Oncology Nursing Forum, 19, 1545–1550.

Noddings, N. (1984). Caring, a feminine approach to ethics and moral education. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Steeves, R., Cohen, M.Z., & Wise, C.T. (1994). An analysis of critical incidents describing the essence of oncology nursing. Oncology Nursing Forum, 21, 19–25.

van Rooyen, D., le Roux, L., & Kotzé, W.J. (2008). The experiential world of the oncology nurse. Health South Africa Gesondheid, 13(3), 18–30.

Vioral, A.N. (2011). Filling the gaps: Immersing student nurses in specialty nursing and professional associations. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 42, 415–420.

About the Author(s)

Bonnie Raingruber, RN, PhD, is a nurse researcher in the Center for Nursing Research and Terri Wolf, RN, MS, is a nursing and quality coordinator for the Cancer Care Network, both at the University of California Davis Medical Center in Sacramento. The authors take full responsibility for the content of the article. The authors did not receive honoraria for this work. The content of this article has been reviewed by independent peer reviewers to ensure that it is balanced, objective, and free from commercial bias. No financial relationships relevant to the content of this article have been disclosed by the authors, planners, independent peer reviewers, or editorial staff. Raingruber can be reached at bjraingruber@ucdavis.edu, with copy to editor at CJONEditor@ons.org. (Submitted June 2014. Revision submitted July 2014. Accepted for publication August 2, 2014.)