Do I Have Hope? Framing End-of-Life Care Discussions

As we in the oncology field know, EOL care is the term used to describe the symptom management, caregiver support, and decisions related to medical care before and surrounding the time of death. This care does not just happen in the moments before breathing stops and the heart ceases to beat. Rather, patients are often living with chronic illness for weeks, months, and sometimes years before death occurs. The opportunity for introductory and, sometimes, profound discussions can spontaneously arise during routine care. These discussions may include individual and family values, cultural traditions, faith and spiritual beliefs, and the legal and economic issues facing the patient at EOL.

Jump to a section

The Expert Panel on Global Health Delivery (GHD) met online in October 2015 and I was invited to serve as a panel member to discuss end-of-life (EOL) care conversations. During the week of meetings, 4 panel members and 63 global participants shared their experiences and perspectives on EOL care (http://bit.ly/1iCV6pC).

As we in the oncology field know, EOL care is the term used to describe the symptom management, caregiver support, and decisions related to medical care before and surrounding the time of death (Institute of Medicine, 2014). This care does not just happen in the moments before breathing stops and the heart ceases to beat. Rather, patients are often living with chronic illness for weeks, months, and sometimes years before death occurs.

The opportunity for introductory and, sometimes, profound discussions can spontaneously arise during routine care. These discussions may include individual and family values, cultural traditions, faith and spiritual beliefs, and the legal and economic issues facing the patient at EOL. Thirty years ago, I would have welcomed the information shared at the GHD meeting. My patient, S.T., was a 56-year-old woman who was in recovery after an open and close surgery six hours earlier for widespread metastatic colon cancer. It was the quiet time of the night—a 4 am check to assess her pain, dressings, nasogastric tube, IV, and vital signs; in other words, routine care. I asked S.T. about her pain level, thinking she would probably want and/or need pain medication. Instead, her response caught me off guard: “Do I have any hope? What will my family do?”

The patients know. Maybe from the look on the residents’ faces . . . or ours. How do we respond?

A survey of 1,067 Americans, aged 18 years and older, found that 9 of 10 people thought it was important to discuss EOL care wishes with loved ones. However, only 24% had talked with loved ones about their EOL care (Conversation Project, 2013). Because many people do not share their preferences, the majority of Americans die in institutional settings despite a desire to die at home (American Psychological Association, n.d.), an indicator of the current gap between patients’ goals and desires and conversations about EOL care.

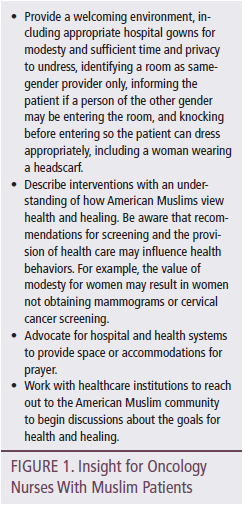

However, we do have guidance and guidelines from many organizations to help direct these conversations with our patients and their family members. Ariadne Labs has developed a program to guide clinicians on how to communicate with seriously ill patients regarding the EOL preferences. The Serious Illness Care Program can be found at http://bit.ly/1HqZ6A4. Advanced Care Planning Decisions, cofounded by Angelo E. Volandes, MD, and Aretha Delight Davis, MD, is designed to empower patients and family members to participate in decisions about their health care. More information on that program can be found at http://bit.ly/1MyUfOz. Other resources and publications can be found in Figure 1.

In addition, starting on January 1, 2016, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services will begin reimbursement for physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants for talking to patients about preferences for EOL care. Details of the plan can be found at http://go.cms.gov/1LHxBWY. Finally, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges (2015), 136 medical schools include EOL care as a required course and 94 schools offer it as an elective course. According to Dickinson (2007), the average total offering of EOL curriculum in baccalaureate nursing programs was 15 hours. Although we do not have more recent statistics for nursing curriculum, we know that educational initiatives such as the End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium have trained more than 19,000 nurse educators in all 50 states (City of Hope, 2015).

During the GHD online discussion on EOL care, Christian Ntizimira, MD, a palliative care physician and pain policy advocate from Rwanda, described an approach to these conversations that encompasses an Ubuntu philosophy: “I am what I am because of who we all are.” Or, “I am a person through other persons.” It speaks about our interconnectedness.

Today, I am less afraid but always in awe of how powerful these conversations are for my patients and for me. This may be the toughest, most important work we do with our patients. As oncology nurses we have the distinct honor to be a part of these stories, hear these questions, and hold the hands of people in the middle of the night. We can honor these conversations by learning more about how to have these EOL conversations (there is more than one way) and how to help our patients write the final chapters of their lives.

On that night more than three decades ago, I wish I could tell you that I responded to S.T. in a remarkably therapeutic way and soothed all of her concerns. I did not know what to say. I did what I knew; I sat on her bed and held her hand. I listened. . . . It was a beginning.

Today, we have the tools to guide these conversations and the support from our professions, organizations, and colleagues to help address the preferences and concerns of our patients. We have resources to help patients and their families start these conversations before a crisis. Hope lies in the important opportunity to address EOL care preferences. We can start these conversations and listen.

In this issue of the Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, an article by Coyle et al. (2015) discusses a communication skills training program for oncology nurses to increase their confidence in having EOL care discussions. Nurses often have opportunities to talk with their patients and begin these conversations—even by flashlight. With the increased public awareness and now government recognition of the value of these discussions, we can use these resources to improve our confidence in communicating about EOL care preferences and share this information with our patients and their families.

References

American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Fact sheet on end-of-life care. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/pi/aids/programs/eol/end-of-life-factsheet.pdf

Association of American Medical Colleges. (2015). Number of medical schools including topic in required courses and elective courses. Retrieved from https://www.aamc.org/initiatives/cir/406462/06a.html

City of Hope. (2015). End-of-life nursing care has evolved worldwide. Here’s how. Retrieved from http://www.cityofhope.org/blog/end-of-life-care-elnec-nursing-education

Conversation Project. (2013). New survey reveals conversation disconnect: 90 percent of Americans know they should have a conversation about what they want at the end of life, yet only 30 percent have done so. Retrieved from http://theconversationproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/TCP-Survey…

Coyle, N., Manna, R., Shen, M.J., Banerjee, S.C., Penn, S., Pehrson, C., . . . Bylund, C.L. (2015). Discussing death, dying, and end-of-life goals of care: A communication skills training module for oncology nurses. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 19, 697–702.

Dickinson, G.E. (2007). End-of-life and palliative care issues in medical and nursing schools in the United States. Death Studies, 31, 713–726.

Institute of Medicine. (2014). Dying in America: Improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/1OW5Tt8

About the Author(s)

Lisa Kennedy Sheldon, PhD, APRN, BC, AOCNP®, is an assistant professor at the University of Massachusetts–Boston and an oncology nurse practitioner in the Cancer Center at St. Joseph Hospital in Nashua, NH. The author takes full responsibility for the content of the article. No financial relationships relevant to the content of this article has been disclosed by the editorial staff. Kennedy Sheldon can be reached at CJONEditor@ons.org.