Communication Skills: Use of the Interprofessional Communication Curriculum to Address Physical Aspects of Care

Background: The literature has emphasized the importance of effective communication regarding psychosocial needs; however, other aspects of patient care, including attention to physical needs, are equally important.

Objectives: The aims of this article are to (a) describe an Interprofessional Communication Curriculum (ICC) in oncology, (b) detail the curriculum content specifically focused on physical aspects of care, and (c) illustrate the importance of interprofessional care in oncology.

Methods: The ICC is organized by the 8 domains of the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care and centers on communication skills needed in oncology clinical practice.

Findings: Based on initial pilot data, oncology clinicians indicate a high level of satisfaction with the ICC. Additional future training courses supported by the National Cancer Institute will prepare oncology teams to enhance communication with patients and families.

Jump to a section

Communication is the cornerstone of oncology nursing. Every aspect of cancer care, from diagnosis through treatment, remission, long-term survivorship, or end-of-life care, depends on excellent communication among the patient, family, and all clinicians involved in care (Paice, 2019). Oncology nurses are a constant presence across this trajectory and in all settings of care. Communication about symptoms and physical status is critical, including during follow-up care of long-term cancer survivors (Paice et al., 2016) and in supporting family members (McHugh & Buschman, 2016).

Effective communication is associated with patient understanding and adherence to the treatment regimen, respect for cultural diversity, and acknowledgment of psychological and spiritual concerns associated with serious illness. Quality communication is also associated with improved patient and family satisfaction with care. Palliative care as a specialty practice has made communication a concern and has prioritized communication training for all disciplines (Donesky et al., 2020; Pfaff & Markaki, 2017; Stajduhar & Dionne-Odom, 2019).

The literature has emphasized the importance of communication for psychosocial concerns, such as breaking bad news and listening to patients’ fears and concerns regarding death, grief, or family distress (Ferrell & Paice, 2019). However, there is also increasing recognition that communication is important for aspects of care beyond psychosocial issues. One area that has received less attention is the domain of physical care. For example, communication skills are needed for the assessment of patients’ symptoms and physical concerns, including sleep, nutrition, and functional status. Enhancing communication skills for physical care will improve symptom assessment, patient education on symptom management, prevention of adverse events, and effective clinician understanding of the physical impact of illness and treatment for each patient and family. Enhanced communication skills may, ultimately, even contribute to the completion of potentially curative cancer treatment (Kreps & Canzona, 2016; Mazor et al., 2016).

This article reviews essential elements of communication applied to physical aspects of care, with suggestions for clinical skills for nursing practice. The content is based on a National Cancer Institute (NCI)–funded training program initiated in 2020, the Interprofessional Communication Curriculum (ICC). Methods of teaching clinicians about better communication skills for physical care are described, as well as initial evaluation data based on pilot use of the curriculum. A case study is provided to illustrate the importance of effective nursing communication in addressing the physical needs of patients with cancer.

Methods

Communication to Assess and Respond to Physical Needs

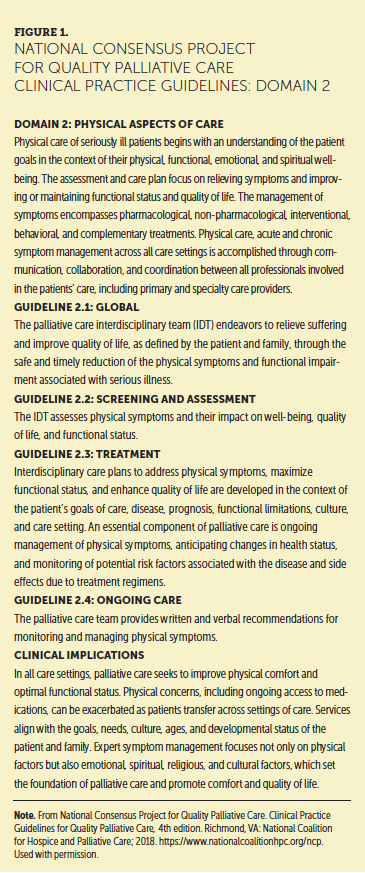

The National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care (NCP, 2018) created clinical practice guidelines to promote best practices for serious illnesses such as cancer. These guidelines have been endorsed by the Oncology Nursing Society and more than 80 other organizations, and they encompass care of children and adults. The guidelines are organized according to eight domains, or dimensions, of care. Physical Aspects of Care is the second domain. Figure 1 presents this domain and the four key guidelines within the domain. As stated in the guidelines, communication is essential for “understanding of the patient goals,” and physical care, including symptom management, “is accomplished through communication, collaboration, and coordination between all professionals” (NCP, 2018, p. 13).

Each of the four clinical practice guidelines for domain 2 describes the importance of communication in physical care. Physical concerns are closely intertwined with emotional, spiritual, religious, and cultural factors, which further emphasizes the need for communication. Physical symptoms common in cancer, such as nausea, dyspnea, and fatigue, are complex problems with intense emotional components and meanings (Collett & Chow, 2019; Donesky, 2019; Mooney et al., 2019; O’Neil-Page et al., 2019). Assessment of these symptoms requires physical examination and evaluation and also includes exploring the meaning of the symptom and its impact on quality of life.

The NCP guidelines also emphasize communication between professionals. For example, nurses routinely assess patient problems, such as pain, but then must accurately and effectively communicate that assessment to other providers to facilitate symptom management decisions (Institute for Healthcare Improvement, n.d.; Lovell & Boyle, 2017). Nurses assess the cultural or spiritual aspects of symptoms to best communicate with interprofessional colleagues in social work or chaplaincy and to facilitate the effective transfer of patients across settings of care (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ], 2020; Collett & Chow, 2019).

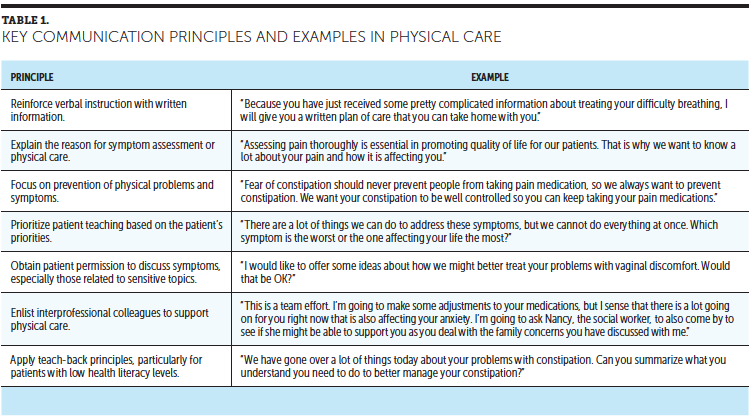

The field of health communication has developed key principles for communication in illnesses such as cancer. Table 1 presents some of these key communication principles applied to physical care, as well as examples of useful language for clinicians. These communication principles are similar to many basic patient teaching principles familiar to oncology nurses, such as using both written and verbal communication, prioritizing patient needs, and recognizing the sensitivity of many issues common in patient interactions. Use of structured symptom assessment tools can also be helpful to guide conversations and consistently assess symptoms (Ferrell & Paice, 2019; Hui & Bruera, 2017).

Communication is particularly important for patients who may have limited health literacy, including patients for whom English is a second language, patients with hearing impediments (AHRQ, 2020), and patients with low health literacy levels (Thomas & Malhi, 2017). Terms that are commonly used in discussing symptoms may seem standard to clinicians but may be unfamiliar to patients. It is important for clinicians to recognize that low health literacy can impair a patient’s ability to understand and follow medical advice. Low health literacy is not always associated with low literacy. Although a patient may be literate, this does not mean that they can understand or articulate medical information to the level that it is communicated between clinicians. Applying communication skills, such as using plain language and asking patients to explain what they know or what they understand, can help clinicians minimize miscommunication when interacting with patients (Christensen, 2016; MacLeod et al., 2017).

One of the most common fears among patients with cancer and their family members is loss of control (Donesky, 2019). This is particularly true when patients are in the home setting and are managing complex cancer treatments and symptom regimens with the help of family members (Donesky, 2019; Hui & Bruera, 2017). Lack of familiarity with medications, procedures, hygiene, and other physical needs compounds feelings of stress. Uncontrolled symptoms, including profound fatigue, nausea, constipation, loss of bowel or bladder control, and dyspnea, can be major factors in the development or worsening of psychological symptoms, such as anxiety or depression. Providing optimum assessment and symptom management can improve patients’ sense of control because they will have a greater understanding of their symptoms and treatment options. Patients with mild or moderate symptoms may fear that symptoms will become worse or uncontrollable, and these fears may greatly increase suffering (Paice, 2019).

Interprofessional Communication Curriculum

The ICC is an NCI-funded professional training program that focuses on communication training in oncology. It is a three-day, in-person train-the-trainer program designed for healthcare professional teams in three oncology disciplines: nursing, social work, and chaplaincy. Professionals from these disciplines are critical to providing psychosocial and physical support in cancer centers and are role models of the best care available for patients. Each participating team consists of two clinicians from different disciplines (e.g., nurse and chaplain, social worker and nurse). Based on results from pilot testing, these three disciplines involve similar needs and competencies.

The ICC focuses on communication skills needed in oncology clinical practice. Using a goal-directed method of teaching, the curriculum places significant importance on providing nurses, social workers, and chaplains with the skills and tools necessary to enact skills-based trainings at their home institutions. Tools used in the course include role-play, case studies, and guides for family conferences and patient communication. Course faculty are senior leaders from the three disciplines, with expertise in communication. The NCP’s (2018) eight domains for quality palliative care form an evidence base for the curriculum.

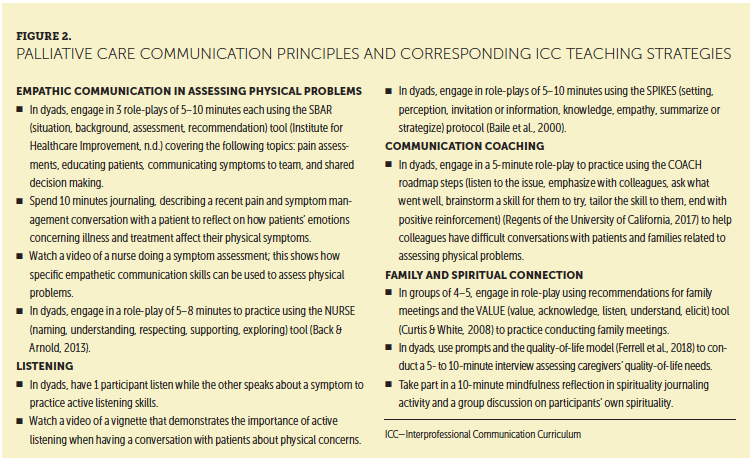

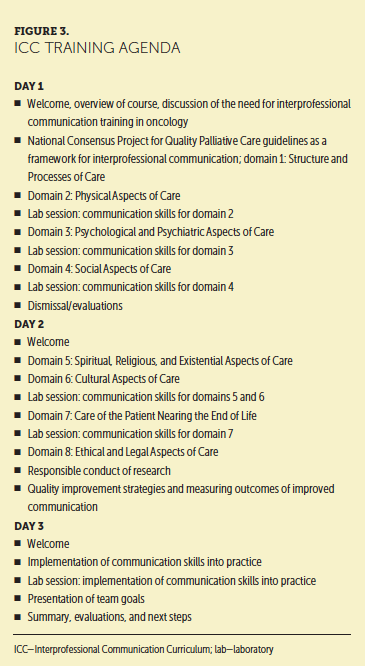

Participating interprofessional faculty members use a variety of teaching methods, including lectures with evidence-based information, discussion sessions, and small-group exercises. To promote further distribution of the educational materials, participants are provided with multiple learning resources, such as lecture notes, slides, and activities for use in training colleagues at their home institutions, in addition to information facilitating best teaching practices and advice. This training primarily prepares participants to serve as competent communication trainers at their respective institutions; it also readies them to act as clinical resources to address common patient concerns (e.g., symptom assessment and management, spiritual and cultural needs); offer psychosocial support to colleagues and to patients and their families; and facilitate interprofessional family meetings. In addition, the training highlights the specific communication skills needed to provide exceptional physical care. There will be five training courses each year, with the first scheduled for January 27, 2021. The NCI training grant pays for course registration, a travel stipend, and all teaching materials. Figure 2 describes communication teaching strategies used in the ICC to support communication in physical care (Back & Arnold, 2013; Baile et al., 2000; Curtis & White, 2008; Institute for Healthcare Improvement, n.d.; Regents of the University of California, 2017). Figure 3 presents the three-day course agenda.

Prior to workshop acceptance, participants are required to submit letters from their supervisors or leadership to support their attendance at the in-person training. In addition, each team of two is required to identify written goals for implementing communication skills training at their own institutions. Postcourse follow-up evaluations concerning goal achievement are conducted at 6 and 12 months to determine barriers, successes, and solutions to problems.

An online version of the ICC enhances the in-person curriculum. Access to the online learning modules is provided to course participants prior to the in-person training, and participants are required to review all online modules before the course starts. The online version includes six modules adapted from the in-person curriculum.

Evaluation

The ICC evolved from a course focused primarily on nurses and was expanded for an interprofessional audience. Pilot course evaluation data identified strengths of the curriculum and its acceptability for education in various clinical settings. A course convened in January 2018 for clinicians in California involved 46 participants (23 dyads consisting of nurses, physicians, social workers, and chaplains) from 26 institutions. In the postcourse evaluation, participants reported high satisfaction (score of 4.8 on a scale of 1 [lowest rating] to 5 [highest rating] for meeting participants’ expectations). Using a scale of 1 (lowest rating) to 10 (highest rating), teams gave the psychosocial skills of staff at their own institutions a mean score of 6.7; there was strong agreement that education was needed to improve staff communication skills.

At nine months after the course, the teams reported having trained 1,246 clinicians in their settings and having made institutional changes, such as improving processes for family conferences and developing communication tools for clinicians in areas such as advance care planning and bereavement support (Ferrell et al., 2019). The curriculum has also been used in courses focused primarily on nurses. Each of the eight domains in the curricula was rated at 4.7 or higher on a scale ranging from 1 (lowest rating) to 5 (highest rating); participants rated each domain to indicate its usefulness to their practice. In addition, participants reported that they valued the course’s diverse educational experiences, such as role-play, video-recorded communication scenarios, lectures, and interactive learning.

The five national trainings will include 6- and 12-month postcourse evaluations of goals for implementing the curriculum. This will include assessment of practice changes, such as strategies to improve patient education and family conferencing, and self-evaluation of improved communication skills.

Case Study

Effective Communication to Meet Physical Needs

M.A. is a nurse practitioner in a medical oncology clinic who is seeing G.E., a 55-year-old woman who has recently completed initial chemotherapy for stage IV lung cancer. Through the clinic visit and physical examination, M.A. notices that G.E. seems anxious and that she appears to have worsening dyspnea.

After completing G.E.’s examination and entering clinic notes into the bedside computer, M.A. moves her cell phone to silent mode, sits next to G.E., and asks if they could spend a few moments talking about G.E.’s symptoms. M.A. begins by stating, “I am a little worried about you. It seems like you are maybe having a little more trouble catching your breath. Can you tell me how things are really going for you?” M.A. focuses on being very attentive to G.E., making eye contact, being comfortable with silence, and listening intently.

G.E. admits that she is having trouble catching her breath, and this worries her because she is hopeful she may be able to enter a clinical trial and does not want the oncologist to think her condition is getting worse. M.A. asks, “How is this trouble with your breathing affecting you? Your quality of life?” G.E. explains that she is not able to “do her chores,” like cooking or helping with her grandchildren.

M.A. is silent, because she senses there are other concerns, and G.E. then says, “I don’t feel useful if I cannot take care of my home or my grandchildren.” M.A. acknowledges those feelings as common, suggesting that better control of the dyspnea may help with her feelings of usefulness to her family. M.A. also makes a mental note to ask the social worker if there are resources available to validate G.E.’s usefulness to her family throughout her life.

M.A. expresses her understanding of G.E.’s concerns and assures her that these symptoms are important and that focusing on her quality of life is a priority. She reinforces that the entire team wants to help G.E. gain control of her symptoms so she can receive all available treatments. M.A. reviews basic teaching about dyspnea, including demonstrating the use of breathing techniques, explaining the need to report fever or cough, and discussing the medications she has prescribed to treat the dyspnea but that G.E. has not yet tried, including an inhaler. M.A. explores barriers to using these medications and learns that G.E. was never instructed on how to use the inhaler and that she was saving it “for emergencies.”

She then tells G.E. that she would like to talk with the oncology team about their conversation and will follow up with a telephone call. M.A. gives G.E. a written summary of the key points of their conversation and reinforces that helping with her symptoms is one of the most important parts of her cancer care. She also asks, “What questions do you have about the things we have talked about today?”

Case Discussion

Many aspects of effective communication are illustrated in this case study, including attentive listening, exploration of the patient’s experience and perspectives, and use of nonverbal communication. M.A. also employs open-ended questions and assesses G.E.’s goals for her care. In addition, she uses a written summary of her teaching and ends with an invitation for G.E. to express other concerns.

Implications for Nursing

Communication has long been and will remain at the core of oncology care. When clinicians are well trained in communication skills, excellent communication between patients and providers is possible. All aspects of patient care, including physical needs and symptom management, can be improved through attention to communication.

Conclusion

Communication skills will continue to be essential for professional practice in oncology and will become even more important given the demands of a burdened healthcare system. Communication training can provide clinicians with the necessary communication skills to effectively engage in conversations regarding symptom management and the physical needs of patients. The ICC can equip clinicians with the tools needed to serve as clinical resources and to help them address common patient concerns related to communication. Ultimately, the ICC will prepare nurses, social workers, and chaplains in adult oncology practice to serve as competent communicators at their institutions.

About the Author(s)

Betty Ferrell, RN, PhD, MA, FAAN, FPCN, CHPN, is a professor and director, and Haley Buller, MSHSC, is a research supervisor, both in the Division of Nursing Research and Education at City of Hope National Medical Center in Duarte, CA; and Judith A. Paice, PhD, RN, is the director of the Cancer Pain Program in the Division of Hematology-Oncology in the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago, IL. The authors take full responsibility for this content. This work is supported by an R25 training grant (1R25CA240111-01A1), Interdisciplinary Communication Training in Oncology from the National Cancer Institute (Ferrell, principal investigator). The article has been reviewed by independent peer reviewers to ensure that it is objective and free from bias. Ferrell can be reached at bferrell@coh.org, with copy to CJONEditor@ons.org. (Submitted April 2020. Accepted June 5, 2020.)

References

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2020). AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit. http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/quality-resour…

Back, A.L., & Arnold, R.M. (2013). “Isn’t there anything more you can do?”: When empathic statements work, and when they don’t. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 16(11), 1429–1432. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2013.0193

Baile, W.F., Buckman, R., Lenzi, R., Glober, G., Beale, E.A., & Kudelka, A.P. (2000). SPIKES—A six-step protocol for delivering bad news: Application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist, 5(4), 302–311. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.5-4-302

Christensen, D. (2016). The impact of health literacy on palliative care outcomes. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing, 18(6), 544–549. https://doi.org/10.1097/NJH.0000000000000292

Collett, D., & Chow, K. (2019). Nausea and vomiting. In B.R. Ferrell & J.A. Paice (Eds.), Oxford textbook of palliative nursing (5th ed., pp. 149–162). Oxford University Press.

Curtis, J.R., & White, D.B. (2008). Practical guidance for evidence-based ICU family conferences. Chest, 134(4), 835–843. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.08-0235

Donesky, D. (2019). Dyspnea, cough, and terminal secretions. In B.R. Ferrell and J.A. Paice (Eds.), Oxford textbook of palliative nursing (5th ed., pp. 217–229). Oxford University Press.

Donesky, D., Anderson, W.G., Joseph, R.D., Sumser, B., & Reid, T.T. (2020). TeamTalk: Interprofessional team development and communication skills training. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 23(1), 40–47. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2019.0046

Ferrell, B., Buller, H., Paice, J., Anderson, W., & Donesky, D. (2019). End-of-life nursing and education consortium communication curriculum for interdisciplinary palliative care teams. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 22(9), 1082–1091. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2018.0645

Ferrell, B.R., Kravitz, K., Borneman, T., & Friedmann, E.T. (2018). Family caregivers: A qualitative study to better understand the quality-of-life concerns and needs of this population. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 22(3), 286–294. https://doi.org/10.1188/18.CJON.286-294

Ferrell, B.R., & Paice, J.A. (Eds). (2019). Oxford textbook of palliative nursing (5th ed.) Oxford University Press.

Hui, D., & Bruera, E. (2017). The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System 25 years later: Past, present, and future developments. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 53(3), 630–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.10.370

Institute for Healthcare Improvement. (n.d.). SBAR tool: Situation-background-assessment-recommendation. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/SBARToolkit.aspx

Kreps, G.L., & Canzona, M.R. (2016). The role of communication and information in symptom management. In E. Wittenberg, B.R. Ferrell, J. Goldsmith, T. Smith, S.L. Ragan, M. Glajchen, & G. Handzo (Eds.), Textbook of palliative care communication (pp. 119–126). Oxford University Press.

Lovell, M., & Boyle, F. (2017). Communication strategies and skills for optimum pain control. In D.W. Kissane, B.D. Bultz, P.N. Butow, C.L. Bylund, S. Noble, & S. Wilkinson (Eds.), Oxford textbook of communication in oncology and palliative care (2nd ed., pp. 244–248). Oxford University Press.

MacLeod, S., Musich, S., Gulyas, S., Cheng, Y., Tkatch, R., Cempellin, D., . . . Yeh, C.S. (2017). The impact of inadequate health literacy on patient satisfaction, healthcare utilization, and expenditures among older adults. Geriatric Nursing, 38(4), 334–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2016.12.003

Mazor, K.M., Street, R.L., Jr., Sue, V.M., Williams, A.E., Rabin, B.A., & Arora, N.K. (2016). Assessing patients’ experiences with communication across the cancer care continuum. Patient Education and Counseling, 99(8), 1343–1348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2016.03.004

McHugh, M.E., & Buschman, P.R. (2016). Communication at the time of death. In C. Dahlin, P.J. Coyne, & B.R. Ferrell (Eds.), Advanced practice palliative nursing (pp. 395–404). Oxford University Press.

Mooney, S.N., Patel, P., & Buga, S. (2019) Bowel management: Constipation, obstruction, diarrhea, and ascites. In B.R. Ferrell & J.A. Paice (Eds.), Oxford textbook of palliative nursing (5th ed., pp. 186–205). Oxford University Press.

National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. (2018). Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care (4th ed.). National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care. https://bit.ly/3ialc3c

O’Neil-Page, E., Dean, G.E., & Anderson, P.R. (2019). Fatigue. In B.R. Ferrell and J.A. Paice (Eds.), Oxford textbook of palliative nursing (5th ed., pp. 132–139). Oxford University Press.

Paice, J.A. (2019). Pain management. In B.R. Ferrell & J.A. Paice (Eds.), Oxford textbook of palliative nursing, (5th ed., pp. 116–131). Oxford University Press.

Paice, J.A., Portenoy, R., Lacchetti, C., Campbell, T., Cheville, A., Citron, M., . . . Bruera, E. (2016). Management of chronic pain in survivors of adult cancers: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 34(27), 3325–3345. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.68.5206

Pfaff, K., & Markaki, A. (2017). Compassionate collaborative care: An integrative review of quality indicators in end-of-life care. BMC Palliative Care, 16, 65. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-017-0246-4

Regents of the University of California. (2017). IMPACT-ICU. https://www.vitaltalk.org/resources/impact-icu

Stajduhar, K.I., & Dionne-Odom, J.N. (2019). Supporting families and family caregivers in palliative care. In B.R. Ferrell & J.A. Paice (Eds.), Oxford textbook of palliative nursing (5th ed., pp. 405–419). Oxford University Press.

Thomas, B.C., & Malhi, R.L. (2017). Challenges in communicating with ethnically diverse populations: The role of health literacy. In D.W. Kissane, B.D. Bultz, P.N. Butow, C.L. Bylund, S. Noble, & S. Wilkinson (Eds.), Oxford textbook of communication in oncology and palliative care (2nd ed., pp. 265–270). Oxford University Press.