Clinical Oncology Nurse Best Practices: Palliative Care and End-of-Life Conversations

Background: Clinical oncology nurses (CONs) support and guide patients and caregivers by encouraging open dialogue and using effective communication skills. Palliative care (PC) and preparing for the end of life require that CONs apply experienced communication skills that are focused, nuanced, and helpful.

Objectives: The aim of this article is to review communication methods and competencies, which can contribute to a best practices foundation for PC-focused conversations with patients and caregivers.

Methods: Expert CONs provided case studies and responded to clinical scenarios, which illustrated and highlighted communication competencies as applied to PC-focused conversations.

Findings: To establish communication competencies applied during PC-focused conversations with patients and caregivers, CONs can develop, enhance, and apply timely and effective communication skills in clinical oncology practice. To build a foundation for PC-focused communication competencies, nurses can access PC and communication skill resources, including mentoring by expert interprofessional practitioners from PC teams.

Jump to a section

Earn free contact hours: Click here to connect to the evaluation. Certified nurses can claim no more than 1 total ILNA point for this program. Up to 1 ILNA point may be applied to Care Continuum OR Psychosocial Dimensions of Care OR Quality of Life. See www.oncc.org for complete details on certification.

During all phases of the illness trajectory of a patient with cancer, clinical oncology nurses support and guide patients and their caregivers by encouraging open dialogue and using effective communication skills. For nurse, patient, and caregiver conversations about palliative care and end-of-life decisions, nurses can apply advanced communication skills, addressing illness complexities, patients’ and caregivers’ stresses, and patients’ life review with existential insights (Kwame & Petrucka, 2021; Moore et al., 2018; Wittenberg et al., 2018).

By example from the following case studies and accompanying scenarios and responses, three expert clinical oncology nurses applied their seasoned communication competencies to real-world palliative care–focused conversations (Brown et al., 2010). The case studies that follow include having conversations with patients about advance directives, relaying emotionally packed information to family members, and managing conflict among family members about treatment decisions.

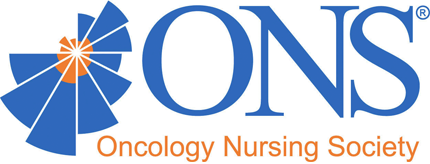

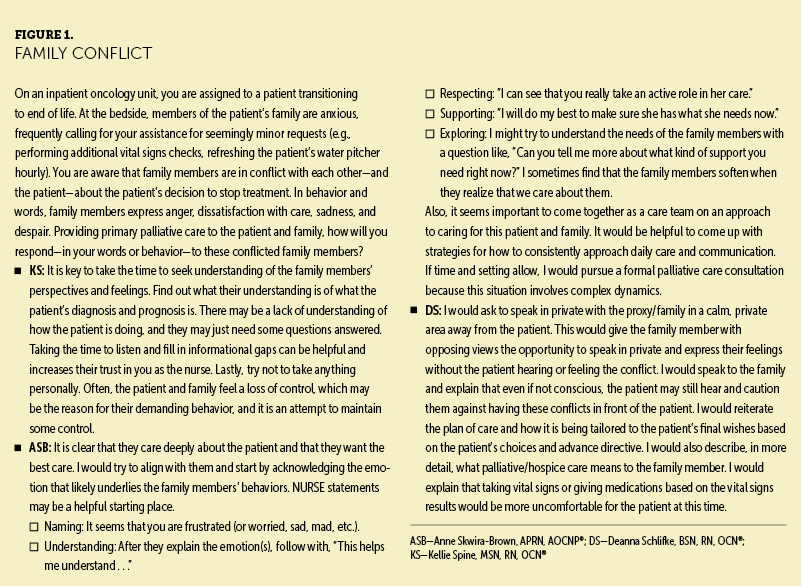

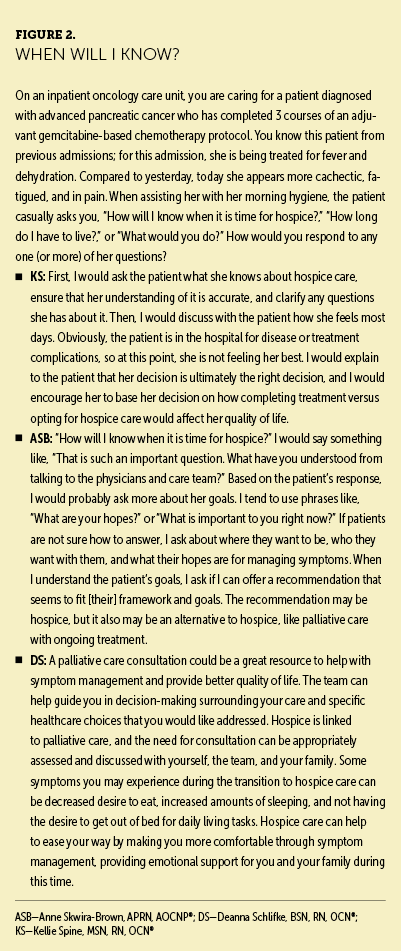

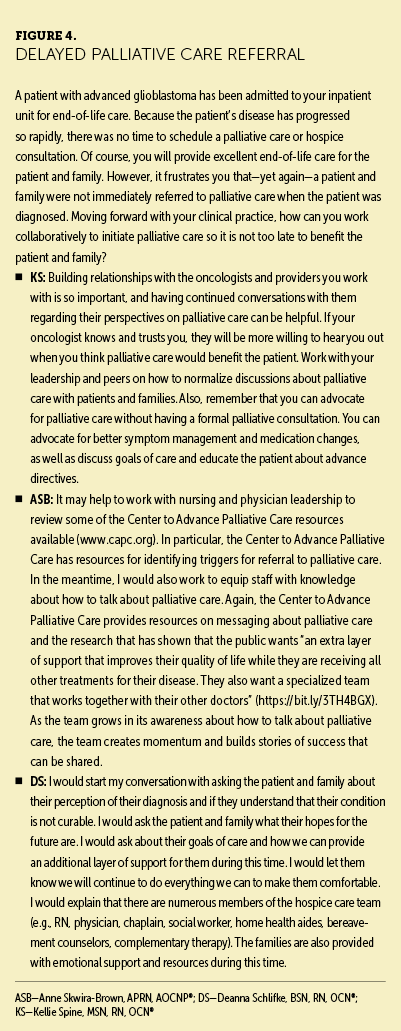

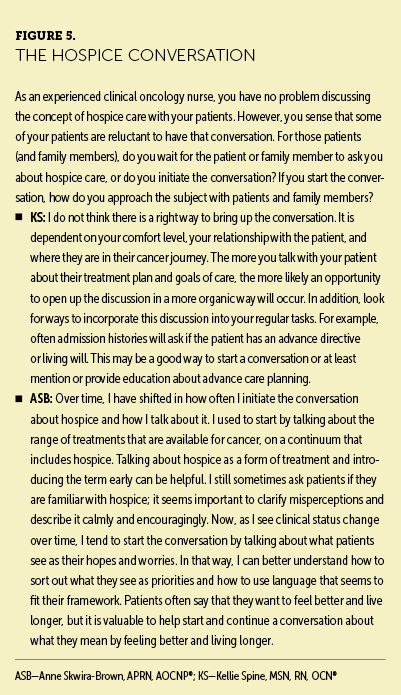

In addition, in Figures 1–5, communication skills applied to palliative care–focused conversation scenarios include the following situations: how to provide clinical care when a patient’s caregivers are anxious, how to handle patient questions about prognosis, what to do when a nurse disagrees with a physician-established plan of care, when and how to introduce the concept of palliative care to a patient and caregivers, and when and how to discuss hospice with a patient and caregivers.

As best practices supporting difficult and often intimate conversations, the case studies and accompanying brief scenario conversations in this article illustrate how a clinical oncology nurse can initiate and continue conversations with patients and their caregivers about palliative care and end-of-life transitions and decision-making (Berg et al., 2021; Wittenberg et al., 2018). It is worth noting that nurses may have different ways of initiating or continuing ongoing conversations; all of these have merit and can be effective.

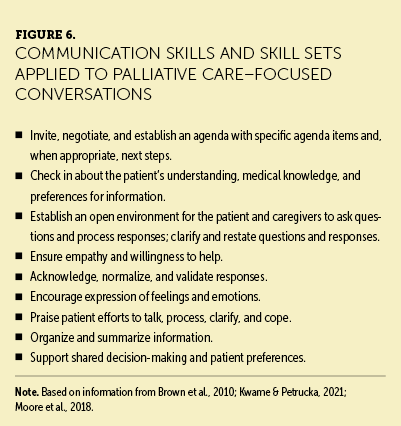

Based on the communication skills highlighted in Figure 6 and palliative care conversation resources (see Figure 7), the content of this article contributes to a scholarly based clinical foundation about palliative care–focused conversations. In addition, these case studies and scenario responses can serve as an initial guide for clinical nurses new to clinical oncology practice, as well as for veteran clinical oncology nurses who seek to refine their communication skills in the context of palliative care (Berg et al., 2021; Moore et al., 2018).

Case Study 1: Discussion With the Patient About Advance Directives

Kellie Spine, MSN, RN, OCN®

Ms. J is a 45-year-old woman with a history of ovarian cancer. She completed treatment two years ago and was considered to be in complete remission. Since then, she has continued to follow up with her oncologist. She recently started experiencing headaches. She called and notified her oncologist of this new onset of symptoms, and she was scheduled to come in for a clinic visit.

During Ms. J’s clinic visit, she was evaluated by her oncologist. No other neurologic abnormalities or signs of recurrence were noted during her assessment. The oncologist ordered MRI of the brain. The MRI revealed a mass, and Ms. J was scheduled back at the clinic to discuss the findings. The oncologist explained to Ms. J that the mass was indicative of an ovarian cancer recurrence with metastasis to the brain.

The oncology nurse, who knows Ms. J well through her initial treatment and follow-up visits, notes that Ms. J does not have an advance directive in place and wants to discuss this with her during this follow-up visit.

The nurse knows that Ms. J is divorced and has three adult children. During her initial treatment, Ms. J’s children were all involved in her care, but the nurse recalls disagreements among the children when it came to decisions about Ms. J’s care. The nurse is concerned that with her recurrence, Ms. J could eventually experience mental status changes that would deem her unable to make decisions about her care.

The nurse has worked in oncology for many years and has unfortunately seen too often that discussions about advance directives with a patient do not happen at all or are brought up too late. Although the nurse knows that discussions about advance care planning can feel uncomfortable to initiate, she is aware of the negative impact a delayed or avoided discussion can have, which can be overwhelming for patients and their family members when decisions feel rushed. Therefore, the nurse decides she will initiate the conversation about advance directives at this visit. She knows that all the members of the healthcare team play a vital role in discussing goals of care but feels that she has the knowledge and a good rapport with the patient to be able to effectively start the conversation (LeBlanc & Tulsky, 2022).

The nurse will use the PAUSE method to help her in discussing the topic of advance directives with Ms. J as follows (VitalTalk, n.d.):

- P: Pause

- A: Ask

- U: Understand

- S: Suggest

- E: Expect

The nurse asks Ms. J how she is feeling hearing about her cancer returning. The nurse offers to answer any questions she has right now and asks if Ms. J needs any support in sharing the news with her children; the nurse offers to talk with any of her children to explain what her treatment plan going forward will look like. Ms. J tells the nurse that she first will talk to her children but that they will likely have more questions; Ms. J would like to give them the nurse’s contact information to better explain the plan of care. Ms. J states that because there are three children, she will have her oldest daughter, Susan, be the contact person so the nurse does not have to discuss the same information with each of them individually.

The nurse says to Ms. J, “Because you mentioned Susan as the point of contact and we are going to be coming up with a plan of care for your recurrence, I wanted to take some time during your visit today to ask if you have thought about who you would want to make medical decisions for you, if for some reason you were not able to. Discussing this topic is something we like to do with all of our patients with a new diagnosis, and with brain involvement, there is a possibility you could become confused. Would you want Susan to be that person?” The nurse knows that normalizing the discussion will make opening up this discussion easier.

Ms. J pauses for a few seconds and says she is not sure. The nurse continues, “Having an advance directive is a way to ensure that your wishes related to your care are carried out. Have you heard of an advance directive?” Ms. J says she is not familiar with advance directives. The nurse goes on to explain to her that when someone does not have an advance directive, healthcare decisions fall on the next of kin, which in Ms. J’s situation would be her children. Because there are multiple children, ideally they can reach a consensus, but if they are not able to, decisions would be based on the majority of her children. The nurse explains to Ms. J that it can be very difficult for families to agree, which may cause delays in care and conflict among family members.

The nurse says to Ms. J, “There are different types of advance directives, but they commonly include a living will, which indicates your wishes regarding your medical care, such as whether you want to receive life-prolonging measures, artificial nutrition/hydration, or cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or donate organs. A power of attorney identifies the person you want to make medical decisions for you, should you be unable to.”

Ms. J expresses she does not want the potential burden of her medical decisions to fall on her children and requests more information on how to initiate an advance directive. Ms. J says, “I am not ready to make any decisions today, but I appreciate you bringing up the conversation because it is not something I had thought about before.” The nurse responds, “I understand that there is a lot to think about and you will need more time and information.”

The nurse prints out a handout that her facility compiled with resources and information on advance directives for Ms. J. Included on the handout is contact information for a social worker who could help facilitate completing an advance directive as well as how to access advance care planning documents to complete, which are available online for each state (CaringInfo, 2022). The nurse also explains to Ms. J that the facility has a palliative care team that can be consulted to help clarify goals of care. The nurse provides a brochure about the palliative care team that outlines the members of the team, including a physician, nurse practitioner, chaplain, social worker, and psychiatrist.

About the Author

Kellie Spine, MSN, RN, OCN®, is an inpatient oncology nurse educator at the University of Louisville Hospital in Kentucky. The author takes full responsibility for this content and did not receive honoraria or disclose any relevant financial relationships. The article has been reviewed by independent peer reviewers to ensure that it is objective and free from bias. Spine can be reached at kellie.spine@uoflhealth.org, with copy to CJONEditor@ons.org. (Submitted June 2022. Accepted August 22, 2022.)

Case Study 2: How Am I Going to Tell My Kids That I Am Dying?

Anne Skwira-Brown, APRN, AOCNP®

Mary is a 63-year-old bookkeeper who underwent surgery and chemotherapy for colon cancer. Treatment-related neuropathy and fatigue complicated her ability to continue working. She was in the midst of filing for disability when she developed pain, nausea, and weight loss. A computed tomography scan showed ascites and liver metastases. After recovering from a paracentesis and inpatient management of nausea and vomiting, she returns to see the medical oncology team with her three adult children to discuss a return to chemotherapy. “She’s a fighter,” they agree as they consider her past cancer treatments and her life as a single mother. After her family members leave the room, the RN, Ella, returns with printed information about the new chemotherapy regimen. Mary looks sadly at the RN and asks, “How am I going to tell my kids that I am dying?”

Although this question sounds cognitive, it is filled with underlying emotion. Ella is alarmed by the question. She sets the patient education materials aside, pulls up a chair, and makes visual contact with Mary. An important starting point for serious illness conversations is to align with the patient by acknowledging the emotions first (Center to Advance Palliative Care [CAPC], 2019a). Not certain what to say next, Ella pauses. Although silence can seem awkward, it can provide a moment for the nurse and the patient to gather their thoughts.

In this situation, Ella remembers the following NURSE acronym (VitalTalk, 2019) and starts with naming and exploring:

- N: Naming

- U: Understanding

- R: Respecting

- S: Supporting

- E: Exploring

The patient’s question is intimidating; however, a desire to be empathetic yields the following simple statement: “That sounds like a really hard thing to be thinking about.” Instead of telling a patient how she feels, Ella floats a hypothesis (VitalTalk, 2019) as follows: “You seem sad.” Pause. “And maybe scared?”

Ella does not have to be correct about the emotion but can remain open when asking questions or making statements. For example, dismissive statements such as, “You do not have to worry about that now,” or opinions such as, “Your children do not seem ready to hear negative information right now,” are not helpful. Just as importantly, after making an empathetic statement, it is important to pause, wait, and listen. A pause may be the most important way to follow an empathetic statement so that the patient has time to hear it, respond to it, and benefit from the conversation (Sheehan, 2018).

Mary cries and describes fear and anger about cancer recurrence. She feels weak, tired, and sick so that she cannot possibly “fight.” The question, “How will I tell my children?” is an emotional cue that belies her underlying worries. A gentle inquiry such as, “Tell me your concerns about talking to them,” can help the patient explore her feelings and can help the nurse to understand the patient’s perception of family coping before offering advice (CAPC, 2019b). Through her tears, Mary admits that she feels guilty that she will no longer be able to protect and provide for them. In addition, she is heartbroken that she will not be able to see her grandchildren as they grow.

At that point, the initial conversation ended. The patient felt heard and supported. Ella and her team worked to become a trusted source of information and support. At a subsequent visit, the nurse practitioner asks the patient for permission, as follows: “So that we are all on the same page, would it be OK to ask some more questions about your children’s understanding of your illness?” Mary admits that she has sheltered them from bad news because they seem to get mad, stop listening, and say that she is giving up. She explains that she is not afraid of dying because of her strong faith.

Mary does not want to have a formal meeting with her children because it seems too stressful. The nurse practitioner encourages her to consider other ways that she can talk to each of them on an individual basis. Helpful phrasing may include the following: “Getting prepared will help you to talk with them. Would you like to talk about how to do that?” (CAPC, 2019a). Initially, Mary does not want to talk about death directly, but she is willing to talk to her children about working out ways to prepare for the worst-case scenario of getting sicker.

Over time, Mary shifts the notion of fighting not to mean battling the cancer but instead to mean fighting for her kids. The family discusses a plan for where she will move when she gets sicker and how they will manage some of the financial issues. Although her children do not share similar views about faith and prayer, Mary talks about the confidence and peace that her faith provides her. They begin to acknowledge how it gives her strength and courage as she faces the worst-case scenario.

Nurses can expect to be caught off guard by surprising or hard questions from patients and caregivers. Instead of an immediate attempt to find a right answer, this case study emphasizes the power of pausing and finding a way to make empathic statements. Patients often need a chance to reflect on how they are feeling or how they may resolve difficult health issues. Using tools, such as the NURSE acronym, can provide reminders to nurses (those new to practice or those with many years of experience) of the types of statements that can help respond to emotions (VitalTalk, 2019).

About the Author

Anne Skwira-Brown, APRN, AOCNP®, is a nurse practitioner at Essentia Health Duluth Clinic in Minnesota. The author takes full responsibility for this content and did not receive honoraria or disclose any relevant financial relationships. The article has been reviewed by independent peer reviewers to ensure that it is objective and free from bias. Skwira-Brown can be reached at anne.skwira-brown@essentiahealth.org, with copy to CJONEditor@ons.org. (Submitted June 2022. Accepted August 22, 2022.)

Case Study 3: Patient and Family in Conflict to Continue Treatment

Deanna Schlifke, BSN, RN, OCN®

J.M. is a 91-year-old man with a history of benign prostatic hyperplasia, renal insufficiency, gross hematuria, and recurrent urinary tract infections. J.M. has a past medical history of congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, and cardiac catheterizations. J.M. is a retired real estate agent and lives at his beach home with his wife and grown daughter.

Secondary to his multiple episodes of gross hematuria and urinary tract infections, J.M. had a cystoscopy, which revealed a bladder tumor; in 2020, he underwent a transurethral resection of the bladder tumor. From pathology evaluation of the tumor, J.M. was diagnosed with muscle-invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder. Many complications arose after this diagnosis. He experienced a cerebrovascular accident on holding his anticoagulation medication for his upcoming bladder procedure, which required hospitalization. J.M. was treated with radiation therapy in combination with IV 5-fluorouracil/mitomycin C and pembrolizumab. Despite completion of treatment, in May 2021, J.M.’s chest computed tomography scan revealed large amounts of pulmonary metastasis. J.M. started on an IV antibody–drug conjugate, enfortumab vedotin, and completed four cycles with a significant decrease in his pulmonary metastasis. J.M. was recently hospitalized for recurrent hematuria and gastrointestinal bleed and had a Watchman left atrial appendage closure device placement and transcatheter aortic valve replacement. During this admission, J.M. was given multiple blood transfusions.

J.M. continues to follow through with his appointments and treatments, but he expresses to the nurses that he is extremely fatigued and that he just wants to relax and spend as much time with his family as he can. He explains to the nurse that he feels that all these nonstop appointments, tests, and treatments are not the way he would like to spend the last chapter of his life. However, he feels that he will be letting down his wife and daughter if he does not continue with the chemotherapy treatments.

J.M.’s daughter, Karen, is a nurse practitioner, and she would like to continue her father’s chemotherapy treatment despite the decline in health status. Karen has arranged for a caregiver to come to the home for 24-hour care for her older adult mother and father. The caregiver takes J.M. to and from his appointments, tests, and treatments, because often Karen is working or home with her mother. Karen is single and does not have any children. Because of J.M’s current plan of care, many nurses caring for him were feeling a sense of moral distress and had reservations about initiating difficult conversations with the family. Because of these clinical staff reservations, the RN and oncologist have a conversation and discuss the need to set up a meeting with J.M. and his family. In preparing for this meeting, the oncologist refers to the Institute for Human Caring (2017) and follows the Serious Illness Conversation Guide.

A meeting is set up for the following afternoon with the oncologist, RN, social worker, patient, wife, and daughter. The Serious Illness Conversation Guide is used as a tool to assist in starting the crucial conversation with the patient and family.

When the physician asks J.M. about his understanding of his illness, the patient explains that he is “tired and approaching the finish line.” J.M. states that his most important goals in his plan of care are to spend time at home with his wife and daughter, rather than continuing with his chemotherapy appointments that are only, in his view, “wasting valuable time.”

Karen and J.M.’s wife are engaged in the conversation. Karen expresses that she is apologetic for failing to consider her father’s true feelings. She states that she is surprised with herself for not beginning these important conversations with her father at the time of his diagnosis, particularly because she is a healthcare professional.

Avoiding these emotionally intense conversations in the beginning may appear to help one cope, but this could lead to moral dilemmas if palliative and end-of-life discussions have not begun, particularly when urgent decisions are necessary. Moral or ethical dilemmas can result in an unpleasant problem or situation for one in not knowing what to do or if they made a right choice. J.M. was placed on palliative care, discontinued his chemotherapy treatments, and is relieved to be spending time at home with his family.

About the Author

Deanna Schlifke, BSN, RN, OCN®, is a nurse manager in the Cancer Center, Breast Center, and Infusion Center at Providence Saint John’s Health Center in Santa Monica, CA. The author takes full responsibility for this content and did not receive honoraria or disclose any relevant financial relationships. The article has been reviewed by independent peer reviewers to ensure that it is objective and free from bias. Schlifke can be reached at deanna.schlifke@providence.org, with copy to CJONEditor@ons.org. (Submitted June 2022. Accepted August 22, 2022.)

Implications for Nursing

Toward providing patient- and family-centered care and improving the patient experience, oncology nursing care includes addressing the patient’s physical needs, providing psychosocial support, and connecting with patients and caregivers on a relationship-based, emotional level. In addition, based on an evolving or established relationship with a patient and their caregivers, the oncology nurse can serve as a trusted source of information and a guide to problem-solving and decision-making.

Integrated into all stages of the patient’s treatment and care, oncology nurses have opportunities to interact in ways that help promote understanding of treatment or no-treatment options and decisions about care. Issues related to goals of care may be particularly difficult to work through as patients near the end of life.

By building and refining communication skills, nurses can interact with and support patients and caregivers, clarifying the plan of care and encouraging a productive decision-making process. As members of interprofessional care teams, nurses can be mindful of previous patient–provider conversations, being congruent with the patient’s care plan. For example, in conversation with the patient, nurses can provide consistent prognostic information to the patient and caregivers, complementing previous conversations they had with members of the interprofessional care team, particularly physicians and advanced practice providers.

As illustrated by the case studies and scenarios in this article, nurses are advised that it takes time to build communication skills to apply to palliative care–focused conversations. Many situations involving palliative care conversations can occur on a regular basis, but not every issue needs to be addressed directly or immediately.

Toward building and refining communication skills to call on during intimate, difficult conversations, nurses can model their own approach to conversations by incorporating behavior and language used by clinical nurse experts and members of palliative care teams. Nurses can also further their competencies by accessing pertinent resources (e.g., communication skills, advance directives, POLST, living wills).

Conclusion

This compilation of case studies and scenarios provides examples of how expert clinical oncology nurses approach palliative care and end-of-life conversations focused on transitions and decision-making. As evident by the breadth of approaches, clinical oncology nurses individualize and differentiate their methods of conversation, depending on the patient’s situation, the topic of conversation, and the patient’s and caregiver’s responses. There are different ways to initiate and continue these crucial conversations.

Over time as a competency of providing palliative care, clinical oncology nurses can build and advance these communication skills so they are timely and effective, supporting patients and their goals of care. Being comfortable and confident with initiating crucial conversations comes with skills, patience, practice, and experience. Supporting a foundation of communication competency, nurses can access palliative care resources, including mentoring by expert interprofessional practitioners from palliative care teams.

About the Author

Ellen Carr, PhD, RN, AOCN®, is the editor of the Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing at the Oncology Nursing Society in Pittsburgh, PA. The author takes full responsibility for this content and did not receive honoraria or disclose any relevant financial relationships. The article has been reviewed by independent peer reviewers to ensure that it is objective and free from bias. Carr can be reached at CJONEditor@ons.org. (Submitted March 2022. Accepted May 17, 2022.)

References

Berg, M.N., Ngune, I., Schofield, P., Grech, L., Juraskova, I., Strasser, M., . . . Halkett, G.K.B. (2021). Effectiveness of online communication skills training for cancer and palliative care health professionals: A systematic review. Psycho-Oncology, 30(9), 1405–1419.

Brown, R.F., Bylund, C.L., Gueguen, J.A., Diamond, C., Eddington, J., & Kissane, D. (2010). Developing patient-centered communication skills training for oncologists: Describing the content and efficacy of training. Communication Education, 59(3), 235–248.

CaringInfo. (2022). Download and complete your state or territories’ advance directive form. https://www.caringinfo.org/planning/advance-directives/by-state

Center to Advance Palliative Care. (2019a). Communication skills: Delivering serious news. https://www.capc.org/training/communication-skills/delivering-serious-n…

Center to Advance Palliative Care. (2019b). Communication skills: Discussing prognosis. https://www.capc.org/training/communication-skills/discussing-prognosis

Institute for Human Caring. (2017). Serious illness conversation guide. https://bit.ly/3zQD4Lm

Kwame, A., & Petrucka, P.M. (2021). A literature-based study of patient-centered care and communication in nurse–patient interactions: Barriers, facilitators, and the way forward. BMC Nursing, 20(1), 158. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-021-00684-2

LeBlanc, T.W., & Tulsky, J. (2022). Discussing goals of care. In J. Givens (Ed.), UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/discussing-goals-of-care

Moore, P.M., Rivera, S., Bravo-Soto, G.A., Olivares, C., & Lawrie, T.A. (2018). Communication skills training for healthcare professionals working with people who have cancer. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 7(7), CD003751.

Sheehan, K. (2018). The power of a pause. Pallimed. https://bit.ly/3hijAZC

VitalTalk. (n.d.). PAUSE talking map. https://www.vitaltalk.org/guides/pause-talking-map

VitalTalk. (2019). Responding to emotion: Articulating empathy using NURSE statements. https://www.vitaltalk.org/guides/responding-to-emotion-respecting

Wittenberg, E., Reb, A., & Kanter, E. (2018). Communicating with patients and families around difficult topics in cancer care using the COMFORT communication curriculum. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 34(3), 264–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2018.06.007