The Meaning of Touch to Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy

Purpose/Objectives: To explore the experience of being touched in people diagnosed with cancer and undergoing IV chemotherapy.

Research Approach: Qualitative, phenomenologic.

Setting: Central New York and northern Pennsylvania, both in the northeastern United States.

Participants: 11 Caucasian, English-speaking adults.

Methodologic Approach: Individual interviews used open-ended questions to explore the meaning of being touched to each participant. Meanings of significant statements, which pertained to the phenomenon under investigation, were formulated hermeneutically. Themes were derived from immersion in the data and extraction of similar and divergent concepts among all interviews, yielding a multidimensional understanding of the meaning of being touched in this sample of participants.

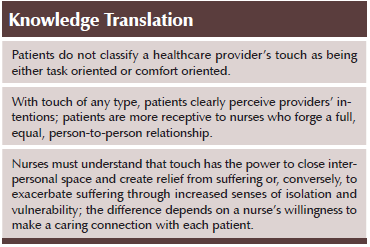

Findings: Participants verbalized awareness of and sensitivity to the regard of others who were touching them, including healthcare providers, family, and friends. Patients do not classify a provider’s touch as either task or comfort oriented. Meanings evolved in the context of three primary themes: building rapport within the healthcare setting, adjusting to changing patterns of touch with family and friends, and intentionally incorporating the therapeutic use of touch.

Conclusions: The experience of being touched encompasses the quality of presence of providers, family, or friends. For touch to be regarded as positive, patients must be regarded as inherently whole and equal. The quality of how touch is received is secondary to and flows from the relationship established between patient and provider.

Interpretation: This study adds to the literature in its finding that the fundamental quality of the relationship between patient and provider establishes the perceived quality of touch. Previous studies have primarily divided touch into two categories: touch that is intended to provide comfort and touch that is incidental to providing care. This distinction was not substantiated by the perceptions of patients in the current study. Participants identified that being viewed as a whole and vital individual in the context of relationships with others, including providers, was fundamental to perceiving any form of touch to be positive, rather than invasive or uncomfortable.

Jump to a section

People diagnosed with cancer face myriad life-changing experiences. For many, these experiences consist of physical discomfort, a bewildering array of medical procedures, dependency on the skill and knowledge of others, and uncertainty regarding the outcome of their illness. The stress of diagnosis and treatment can heighten patients’ awareness of many aspects of daily interactions, including being touched. Touch is a natural impulse as a means to communicate caring and reassurance. This is particularly true in nursing, a field in which touch is a foundation of care. Chang (2001) stated that “touching is approached as a form of communication” and that “physical touch is an essential and universal component of nursing care,” as well as that “nurses touch within the caring perspective” (p. 820).

Touch has the power to close interpersonal space and create relief from suffering or, conversely, to exacerbate suffering through increased isolation and vulnerability. In addition, touch is a more compelling form of contact than sight or hearing because it signifies vulnerability (Gadow, 1984). Touch communicates powerfully and viscerally. Author, activist, and lecturer Helen Keller, who was blind and deaf, can be considered as one of the quintessential observers of the quality of touch.

The hands of those I meet are dumbly eloquent to me. The touch of some hands is an impertinence. I have met people so empty of joy, that when I clasped their frosty finger-tips, it seemed as if I were shaking hands with a northeast storm. Others there are whose hands have sunbeams in them, so that their grasp warms my heart. It may be only the clinging touch of a child’s hand; but there is as much potential sunshine in it for me as there is in a loving glance for others. (Keller, 2004, p. 105)

Consequently, understanding the meaning of touch to patients is critical and requires patients to become the informants. The stories of patients’ lived experience of touch are largely missing from nursing literature. Routasalo (1999) observed that touch may be “so integral . . . that the need for serious research is not recognized,” but that “more research, and qualitative research in particular, is needed to better understand the effects and meaning of touch” (p. 849).

Nursing theory and research regarding touch have primarily focused on categorizing the types of touch that nurses provide in the context of carrying out tasks and providing comfort. In a literature review of physical touch in nursing studies, Routasalo (1999) tabulated 27 categories of physical touch defined by 22 individuals or groups of nurse researchers. Chang (2001), in an observational study of the conceptual structure of physical touch, determined five additional types of touch that were defined as touch “operating in caring situations” (p. 825). However, Routasalo (1999) stated that “the use of multiple categories in research increases the risk of misinterpretation” (p. 848). By categorizing touch associated with tasks into many different groups, a lack of awareness persists regarding the fundamental way in which any touch is an expression of interpersonal regard; as such, the presence or absence of this regard is easily perceived by the patient, regardless of task.

The nursing literature has a surprisingly small number of studies that focus directly on patients’ experiences that could clarify the meaning of touch. O’Lynn and Krautscheid (2011) conducted structured group interviews about patients’ attitudes toward intimate personal care. Interview themes selected by the researchers focused on communication, choices, gender, and professional touch. The most thorough discussion among participants involved “their desire for rapport with the nurse if care involved intimate touch,” with one participant wanting to “make a human connection” (O’Lynn & Krautscheid, 2011, p. 27).

Sundin and Jansson (2003) note that a nurse’s touch can create a feeling of connection for a patient, as well as affirmation of his or her intrinsic value as a person. Similar results were noted by Bottorff (1993) who, using the technique of qualitative ethology, examined video recordings of nurses caring for patients. Bottorff (1993) determined that when a nurse is so moved to use gentleness and concern as part of his or her response to a patient, particularly when doing personal care requiring touch, the patient perceived the interaction in a positive manner. In a phenomenologic study of patients’ accounts of illness, Morse, Bottorff, and Hutchinson (1994) stated that the “performance of routine interventions” itself did not enhance a patient’s comfort; instead, “the interventions were being done for the patient and with the patient and not simply to the patient” (p. 191).

Within a cultural context, patient perceptions of being touched include a deep level of interpersonal communication and wholeness. An ethnographic study by Morales (1994) found that hospitalized Puerto Ricans with cancer viewed a nurse’s touch as enhancing their coping abilities and conveying “acceptance of the patient as person, both of which lead to patient confidence” (p. 468). Chang (2001), in a study of Korean healthcare professionals and patients, noted that the “concept of physical touch emerged as a complex phenomenon having meanings on several different dimensions and structures” (p. 823). In addition, Chang (2001) observed that the “physical touch in caring as a behavioural process of skin-to-skin contact between people is based on commitment to humanism . . . through which physical and emotional comfort is promoted and spirituality is shared” (p. 824).

The current article describes a phenomenologic study exploring the meaning of touch to patients who were diagnosed with cancer and actively undergoing treatment with IV chemotherapy. The study focused on the patients’ perceptions of being touched following diagnosis and during treatment. Statements of the participants clearly articulate their perception that the quality of touch is not limited to situations in which comfort is being offered. Their perceptions of being touched transcend the situation in which touch is being given; the ability to convey positive regard and caring depends largely on the healthcare provider.

Methods

Design

Phenomenology, particularly the perspective developed by Merleau-Ponty (1962), has been used in the current study as the philosophic mode of inquiry. It is also “the study of human experiences” (Sokolowski, 2000, p. 2) and the way these experiences influence perceptions of being in the world. Emphasis is placed on the essential nature of human experience being situated within a unique body (Wilde, 1999b). The lens of Merleau-Ponty (1962) focuses clearly on the importance of embodied existence (Wilde, 1999b) and is a perfect fit for the study of lived, or embodied, meaning of touch in people diagnosed with cancer.

Phenomenologic methods incorporate open-ended questions during individual interviews to elicit the essential experience of a phenomenon to the participant without predetermined parameters. This allows participants to define what they consider essential to the topic of exploration. Because Merleau-Ponty (1962) does not specify a detailed method of data interpretation in his work, the methods used in the current study followed the linear steps in conducting phenomenologic research described by Colaizzi (1978) and the content analysis described by van Manen (1990). van Manen’s (1990) approach to hermeneutic phenomenology was used as a guide to deepen the process of understanding the experience and eliciting meanings of the experience (Wilde, 1999a).

Setting and Sample

Following approval from the institutional review board of the State University of New York Upstate Medical University in Syracuse, patients who indicated a willingness to participate were referred to the primary author by providers in central New York and northern Pennsylvania, both in the northeastern United States. The study included 11 adults (8 women and 3 men) who met the eligibility criteria of being aged 18 years or older, having been diagnosed with cancer, and undergoing active treatment with IV chemotherapy at the time that consent for participation in this study was obtained. All participants were also required to be fluent in English, fully alert and oriented, able to hear and speak, and able to comprehend and sign informed consent for participation.

Data Collection and Analysis

Participants were each interviewed for about one hour in a place and at a time of their choosing. Pseudonyms were used for confidentiality. Interviews consisted of broad, open-ended questions and were audio recorded. To establish rapport and build a foundation for more detailed questions, initial questions centered on each participant’s discovery of cancer, diagnosis, treatment experiences, and social and personal consequences of the lived experience. Exploration of the initial diagnosis was important because of the life-changing nature of the diagnosis and the accompanying feeling of shock that many people experience at the moment of receiving the diagnosis (American Cancer Society, 2014). Then, the course of treatment was explored, with particular attention paid to situations and experiences involving touch.

Participant interviews were transcribed into Microsoft® Word. Immersion in the data required the primary author to read and listen to each interview simultaneously. This step ensured the correct transcription of the interview and reinforced the primary author’s understanding of the linguistic sense of all portions of the interviews through awareness of the auditory cues.

To identify themes from the individual interviews, each transcript was read by the primary author multiple times to allow further immersion into the participant’s text (Colaizzi, 1978). Significant statements that pertained to the phenomenon under investigation were selected, and the meanings of these statements were formulated hermeneutically by the primary author following the procedures of van Manen (1990).

The primary author then contacted each participant and furnished copies of their transcripts and the significant concepts contained within. Participants were given the opportunity to take part in a follow-up interview to add any new information or correct interpretations of the initial interview; two participants elected to do so. The concepts were then grouped and organized into major themes and subordinate concepts.

Auditability is the practice of providing documents for examination by an independent examiner. The first 10 transcriptions and recordings were reviewed by an independent assistant who audited and confirmed or corrected the transcribed text. The two follow-up interviews and the 11th primary interview were transcribed by an independent transcriptionist, and the content was verified by the primary author. In addition, although all interviews were conducted by the primary author, the 11th interview was conducted by both authors to provide additional auditability and depth to the process of peer debriefing employed to ensure trustworthiness of the data.

Findings

Feeling Whole and Being Touched

Feeling whole and being touched, the overarching, uniting concept of the interviews conducted for the current study, can be expressed by the following statement: Patients want to be regarded by others as themselves—as complete, vibrant individuals—and not as invalids. Being touched has an inextricable relationship with an individual’s sense of being. All 11 participants expressed how various aspects of being touched related to feeling whole and being regarded as such by others.

Three major themes emerged from the participant interviews. The first, building rapport, evolved from touch in the healthcare setting and how it affects the relationship between provider and patient. The second, embracing change, focused on the context of changing patterns of touch by family and friends pre- and postdiagnosis. The third, intentionally therapeutic use of touch, explored situations in which participants received touch intended to be relaxing and provide comfort (e.g., massage therapy, assistance with personal care). Participant quotations regarding aspects of touch in the healthcare setting, aspects of touch from family and friends, and the intentionally therapeutic use of touch can be found in Figures 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

Building Rapport

For each participant, being touched by providers was related to building rapport and enhancing the depth of the patient-provider relationship. The essential desire to be seen as a whole individual on the part of the participant gave each an acute sensitivity to the intention of the provider. The participant’s depth of comfort or discomfort with each touch was influenced by the degree that the provider was able to establish a personal relationship that demonstrated a positive regard and full attention. Without building a rapport that transcends the roles of expert and invalid, touch only serves to create distance and disengagement. A female participant in her late 50s with colorectal cancer mentioned the phrase “participating in you” in relation to touch, which strikes to the heart of the inter-relationship between two people and has a poignant applicability within the healthcare setting.

A genuine rapport builds a solid foundation for touch, which enhances the patient-provider relationship. Being genuine requires providers to engage deeply with their patients and, in turn, gives patients a sense of true participation and control. Even within the invasive process of IV access, provider approaches and uses of touch were perceived in many instances to be gentle or caring. Other attributes of provider interaction that positively influenced the experience of being touched included showing gentleness, respect, caring, concern, and sensitivity to patient comfort level; giving warning before touching in invasive examinations; and allowing the patient to feel a sense of control by taking time for examinations and procedures.

Conversely, experiences with providers that created patient anxiety or were perceived as traumatic were commonly experienced in situations in which patients did not feel fully regarded; procedures and tasks took precedence over the relationship between patient and provider. For example, the power of being gentle and asking permission to touch was striking in the receptivity to examinations of a female patient in her late 40s with ovarian cancer. The patient had a history of childhood sexual abuse and said she was hypervigilant regarding any form of being touched. She found examinations performed by her gastroenterologist and surgeon relatively easy to tolerate because they were gentle and “got it” when she was uncomfortable or asked permission before touching, giving her a sense of control and agency in her own care, which profoundly eased her discomfort.

When the provider is focused on a task and excludes the patient as a coparticipant, interactions are often alienating. Fear and anxiety occur in situations that create a sense of isolation and uncertainty (e.g., undergoing scans or radiation therapy treatments, suffering from severe side effects of treatment). A female patient in her late 50s with colorectal cancer recalled the insertion of a nasogastric tube in the emergency department, an experience that was traumatic primarily because of the absence of allowing the patient any sense of agency or control in the process.

[I was alone and had fallen asleep when the physician] just started, even before I was even awake,. . . ramming a tube down my nose. . . . It was like a nightmare. . . . She didn’t even explain what why or what this was. . . . I asked her to stop; she ignored me. . . . I felt almost stripped naked. . . . No respect for me. . . . [I] felt isolated. . . . It was almost like being raped.

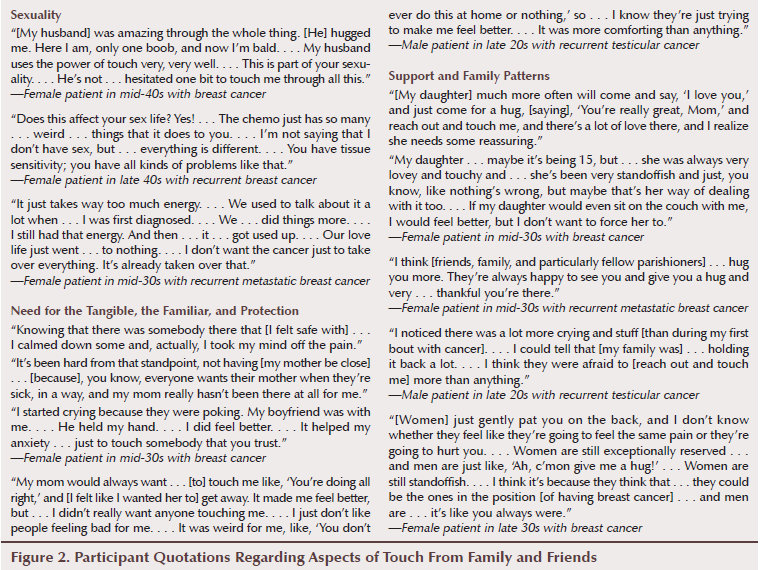

Touch of Family and Friends

Each participant’s response to touch from family and friends reflected the unique expression of vulnerability inherent in their relationships. All participants expressed the desire for normality and wholeness during periods of deep suffering. Being touched was, for most, a tangible form of support. For one female participant in her mid-40s with breast cancer, the support from her husband regarding her sexuality and physical changes after surgery and during chemotherapy brought them much closer. Sexuality encompasses intimate physical and emotional contact. Three participants chose to discuss how undergoing surgery and chemotherapy affected their sexual relationships. Their experiences illustrate the complex interdependency of sexuality with multiple aspects of being in an intimate relationship. Two participants said they continued to have sexual relations with their partners. However, one female participant in her mid-30s with recurrent metastatic breast cancer found that she was just too tired and that her level of fatigue was affecting her relationship with her husband.

For many, the comfort of a mother’s touch is primal. Profound desire for a mother to provide shelter was often expressed by participants, particularly by younger participants whose mothers were still present in their lives. However, the desire for normalcy sometimes conflicts with this desire. The youngest participant in the current study, a man in his late 20s with recurrent testicular cancer, discussed being caught between wanting comfort and wanting to be normal. Although his mother’s touch felt good to him and he craved her touch, he would not let her touch him when he was seriously ill in the hospital; it was a different way for her to behave, and this made him feel more vulnerable.

The patterns of family and friends varied, but many tended to offer more physical support to participants after the diagnosis of cancer. Some participants expressed a strong desire for a form of touch that would evoke feelings of security and protection. One exception was a male participant in his late 30s with colorectal cancer whose family pattern was not physically demonstrative. Instead, support was shown by helping him. This participant said, “I got six brothers, and we never . . . touch each other in any way. . . . [After my diagnosis,] I think everybody changed. . . . All my guy friends . . . they’re not touchy-feely; they mow my lawn.” However, he said the women he knew hugged him much more than before he was diagnosed.

A female participant in her late 30s with breast cancer said women hugged her more lightly than men. She also noticed that women were more reluctant to engage her in conversation in waiting rooms or other public places when they observed her scarf and bald head; she attributed this to their sense of vulnerability when faced with the reality of breast cancer in another woman.

Physical expressions of support included varying degrees of closeness. A female participant in her mid-40s with breast cancer said her family offered enormous physical and emotional support from the earliest news of her diagnosis. Others found that certain family members withdrew from them. A female participant in her mid-30s with breast cancer noted that her daughter and her mother withdrew. She added that her mother’s withdrawal was particularly difficult; the desire for one’s mother when ill is tied intimately to the desire for deep security.

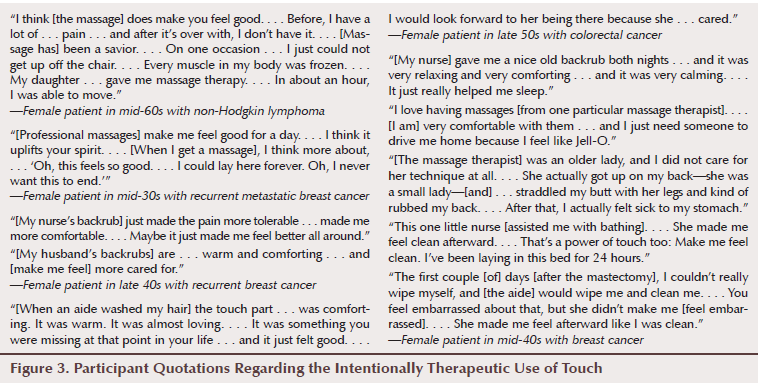

Intentionally Therapeutic Use of Touch

Massages, backrubs, and the delivery of personal care (e.g., assistance with bathing) are all forms of touch that involve the explicit intention to help another person feel better. Several participants said they had generally positive experiences with family or professional massage therapists regarding the intentionally therapeutic use of touch. A female participant in her mid-30s with recurrent metastatic breast cancer received professional massages after surgery and during chemotherapy, which provided relaxation and a general sense of being comfortable in her body, as well as respite from being ill; she explained that the massages uplifted her spirit. Massages given to a female participant in her mid-60s with non-Hodgkin lymphoma by her daughter gave her enormous relief from the deep bone pain that would paralyze her following a pegfilgrastim (Neulasta®) injection.

The intention to provide a caring touch is not sufficient to make a person feel that the touch is beneficial. Having full regard of the wholeness and agency of the patient is key to this type of touch. A female participant in her mid-40s with breast cancer said she receives regular massages from a particular therapist with whom she has developed an excellent professional relationship. However, the participant had previously worked with two other massage therapists who did not listen to what she wanted or used techniques that violated professional boundaries.

For patients, receiving assistance with the most basic and intimate personal care has the potential to create a sense of normality and maintain dignity. Providing this type of touch with caring and integrity is particularly important in the hospital setting. Touch during assistance with bathing or toileting can provide acknowledgement of basic human dignity. Receiving personal care that was gentle and thorough allowed a female participant in her late 50s with colorectal cancer to feel clean and receive care that had been missing at that point in her life.

Discussion

In the current study, the patients’ statements and stories underscore the importance of acknowledging their personhood, independent of provider, venue, or task. Their receptivity to the quality of touch is directly related to the quality of regard on the part of the provider. In contrast to earlier studies, the current study found that patients do not separate the perception of being touched into procedure-oriented touch versus touch intended to provide caring and comfort. In addition, the current study adds to the present body of knowledge by having patients themselves articulate the essential importance of being regarded as a whole and integral human being, independent of their diagnoses.

Many individuals diagnosed with cancer experience great suffering that arises from feelings of loss of independence and being separated from others (Billhult & Dahlberg, 2001; Ferrell & Coyle, 2008). Ferrell and Coyle (2008) explained this suffering as being an intensely personal experience that creates a separation between the patient and the rest of the world. Those diagnosed with cancer “may express intense loneliness and yearn for connection with others while feeling intense distress about dependency on others” (Ferrell & Coyle, 2008, p. 108). Although touch can provide a means to dissolve this isolation and provide comfort and affirmation, it can also reinforce isolation and dependence according to the perceived intention of the patient’s provider, family, or friend.

Human intention cuts through the constructed boundaries of task-oriented touch versus caring touch. Stein (1989) wrote of understanding the communication behind another’s outward expression and postulated about the meaning of phenomenologic intersubjectivity and empathy. The category of “empathetic touch” as described by Gadow (1984)—one in which the mutual interaction is between two people who are “whole and valid”— is at the core of this desire for rapport and for making a human connection (p. 68). According to Gadow (1984), touch provided in the context of “intersubjectivity, affirming in patients the dignity and worth that morally distinguishes persons from objects,” (p. 63) has the power to transform, even if only for a short time, the sense of suffering in another.

This concept reinforces the idea of nursing as a discipline that fully recognizes and embraces the benefits of maintaining focus on patients as people during routine tasks that require touch. Smith (2014) discussed the need for nurses to interact more consciously with patients instead of with the technology or the task, but did not clearly expand on the use of patient-centered touch while accomplishing routine tasks (e.g., blood pressure measurement). In all tasks, creating an essential caring relationship helps patients to rebuild and maintain their integral sense of wholeness in the face of coping with a diagnosis of cancer and its attendant treatments. Almerud, Alapack, Fridlund, and Ekebergh (2008) remarked on the invisibility of patients within a high-tech setting, such as the intensive care unit. In such a setting, “the patient ends up [as] the object of observation,” and nurses “divide technique from human touch” (Almerud et al., 2008, p. 136). Other providers also experience this split when working in highly technical settings and situations (e.g., imaging procedures, radiation therapy, surgical venues). However, treating all patients, regardless of their level of consciousness or functionality, as full, participating human beings is likely to be more critical to their overall well-being than is as of yet acknowledged by the nursing profession. To participate in another person is to fully interact with one’s entire attention as an individual and with total regard for the personhood and individuality of the other.

Limitations

The sample for the current study consisted of a Caucasian, middle-class population from the northeastern United States. Greater understanding of the meaning of touch to all patients would be promoted by conducting additional phenomenologic research with a more diverse set of participants from a broader sample of ethnic and cultural groups, age ranges, geographies, and gender and sexuality, including people in different phases of treatment or who are living with different illnesses. Although the conclusions of studies involving more varied participants generally agreed with many of the current study’s findings, an even greater cultural diversity is needed to enhance understanding of the phenomenon of being touched.

One significant characteristic of the current study participants was their ability and willingness to communicate their experiences. Volunteering to be interviewed selects for a subset of people who are open and articulate. The meaning of being touched expressed by people who are less comfortable speaking with others would enable a much deeper comprehension of the nature of their personal suffering and the manner in which that suffering could be alleviated during the course of treatment.

Implications for Practice

The ability to provide a conscious caring presence is essential for nurses in all settings. It requires a level of self-examination and maturity, particularly for younger nurses faced with the demands of the modern healthcare setting. If nurses do not approach each interaction with their patients in a manner that fully affirms each person’s essential integrity, they will fail to embody the quality that is precious and integral to nursing as a profession. Benner (2004) noted that touch “is invisible, rarely charted, and almost never suggested in a nursing care plan,” as well as that “comforting touch, solace, and presencing (i.e., being present and available to the patient) are left in the region of the art of nursing practice” (p. 346). Genuine engagement with, as well as attention and responsiveness to, the unique qualities of each person who also happens to be a patient is key to the provider being perceived as offering excellent care. The power of intersubjective relationship while carrying out task-oriented touch was related by a female participant in her late 50s with colorectal cancer when she recalled that in the midst of a difficult IV insertion, she felt caring come through the hands of the man who was doing the procedure.

In their study of hope and healing in patients with lung cancer, Eustache, Jibb, and Grossman (2014) discussed mindfulness on the part of providers, noting that they must be “mindful of the whole person, not simply his or her fragmented parts, by helping to navigate the clinical context, assisting in the search for meaning and the rebuilding of hope, and being companions at each step of the healing journey” (p. 506).

The forging of a relationship based on an essential equality between patient and provider permits deeper healing, particularly when touch is incorporated into the ongoing journey. In many cases, hospital nurses are not able to consistently care for a particular patient. However, based on themes taken from interviews with the study participants, even small interactions in which nurses or other providers engage patients as complete and equal human beings have deep meaning and are viewed positively by patients.

Qualitative, phenomenologic research methods designed to use open-ended questions have the power to elicit profound expressions of personal experience regarding particular areas of interest. In the healthcare setting, increased use of qualitative research can help to better define variables to be used with increasingly more specific research designs. Research concerning the provision of massage therapy to people living with a diagnosis of cancer shows widely varying results (Ahles et al., 1999; Lawvere, 2002; Rexilius, Mundt, Erickson Megel, & Agrawal, 2002; Smith, Kemp, Hemphill, & Vojir, 2002; Sturgeon, Wetta-Hall, Hart, Good, & Dakhil, 2009; Toth et al., 2013). Based on findings from the current study, such incorporation of patient-perceived quality of relationship with the massage therapist may add depth and control to similar studies.

Conclusion

Intersubjectivity is clearly perceived by patients in all situations, whether they are undergoing high-tech or invasive procedures, being treated in an examination room, receiving a massage, or being bathed. None of the participants in the current study cited a situation in which disconnected or impersonal care was positively received. Neither the care venue nor the associated tasks were perceived to be separate from the patient’s understanding of how he or she was regarded by a provider.

The phrase “participating in you” underscores the significance of being touched while undergoing medical and nursing procedures to such a degree that no separation exists between positive rapport and a positive experience of being touched during routine care or procedures. The current study yielded the understanding that touch has a much larger meaning to patients than just the physical act. In addition, touch is inextricably related to the quality of relationship with the person touching the patient, particularly in the healthcare setting, as well as among family and friends. As such, those in healthcare settings must augment their roles as providers of tasks by experiencing and affirming the human beingness of self and the other.

References

Ahles, T.A., Tope, D.M., Pinkson, B., Walch, S., Hann, D., Whedon, M., . . . Silberfarb, P.M. (1999). Massage therapy for patients undergoing autologous bone marrow transplantation. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 18, 157–163. doi:10.1016/s0885-3924(99)00061-5

Almerud, S., Alapack, R.J., Fridlund, B., & Ekebergh, M. (2008). Caught in an artificial split: A phenomenological study of being a caregiver in the technologically intense environment. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing, 24, 130–136. doi:10.1016/j.iccn.2007.08.003

American Cancer Society. (2014). The emotional impact of a cancer diagnosis. Retrieved from http://www.cancer.org/treatment/treatmentsandsideeffects/emotionalsidee…

Benner, P. (2004). Relational ethics of comfort, touch, and solace—Endangered arts? American Journal of Critical Care, 13, 346–349.

Billhult, A., & Dahlberg, K. (2001). A meaningful relief from suffering: Experiences of massage in cancer care. Cancer Nursing, 24, 180–184. doi:10.1097/00002820-200106000-00003

Bottorff, J.L. (1993). The use and meaning of touch in caring for patients with cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 20, 1531–1538.

Chang, S.O. (2001). The conceptual structure of physical touch in caring. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 33, 820–827. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01721.x

Colaizzi, P.F. (1978). Psychological research as the phenomenologist views it. In R.S. Valle & M. King (Eds.), Existential-phenomenological alternatives for psychology (pp. 48–71). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Eustache, C., Jibb, E., & Grossman, M. (2014). Exploring hope and healing in patients living with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41, 497–505. doi:10.1188/14.ONF.497-508

Ferrell, B.R., & Coyle, N. (2008). The nature of suffering and the goals of nursing. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Gadow, S. (1984). Touch and technology: Two paradigms of patient care. Journal of Religion and Health, 23, 63–69. doi:10.1007/BF00999900

Keller, H. (2004). The story of my life. J. Berger (Ed.). New York, NY: Random House.

Lawvere, S. (2002). The effect of massage therapy in ovarian cancer patients. In G.J. Rich (Ed.), Massage therapy: The evidence for practice (pp. 57–83). Edinburgh, UK: Mosby.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962). Phenomenology of perception. (C. Smith, Trans.). New York, NY: Humanities Press.

Morales, E. (1994). Meaning of touch to hospitalized Puerto Ricans with cancer. Cancer Nursing, 17, 464–469. doi:10.1097/00002820-199412000-00003

Morse, J.M., Bottorff, J.L., & Hutchinson, S. (1994). The phenomenology of comfort. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 20, 189–195. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1994.20010189.x

O’Lynn, C., & Krautscheid, L. (2011). Original research: ‘How should I touch you?’: A qualitative study of attitudes on intimate touch in nursing care. American Journal of Nursing, 111, 24–31. doi:10.1097/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000395237.83851.79

Rexilius, S.J., Mundt, C., Erickson Megel, M., & Agrawal, S. (2002). Therapeutic effects of massage therapy and handling touch on caregivers of patients undergoing autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Oncology Nursing Forum, 29, E35–E44. doi:10.1188/02.ONF.E35-E44

Routasalo, P. (1999). Physical touch in nursing studies: A literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 30, 843–850. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.01156.x

Smith, G.J. (2014). The ‘soft skills’ of cancer nursing: How to keep the focus on the patient. Oncology Times, 36, 5–6. doi:10.1097/01.COT.0000445152.42957.8f

Smith, M.C., Kemp, J., Hemphill, L., & Vojir, C.P. (2002). Outcomes of therapeutic massage for hospitalized cancer patients. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 34, 257–262. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2002.00257.x

Sokolowski, R. (2000). Introduction to phenomenology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Stein, E. (1989). On the problem of empathy (3rd ed.). (W. Stein, Trans.). Washington, DC: ICS Publications.

Sturgeon, M., Wetta-Hall, R., Hart, T., Good, M., & Dakhil, S. (2009). Effects of therapeutic massage on the quality of life among patients with breast cancer during treatment. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 15, 373–380. doi:10.1089/acm.2008.0399

Sundin, K., & Jansson, L. (2003). ‘Understanding and being understood’ as a creative caring phenomenon—In care of patients with stroke and aphasia. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 12, 107–116. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00676.x

Toth, M., Marcantonio, E.R., Davis, R.B., Walton, T., Kahn, J.R., & Phillips, R.S. (2013). Massage therapy for patients with metastatic cancer: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 19, 650–656. doi:10.1089/acm.2012.0466

van Manen, M. (1990). Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Wilde, M.H. (1999a). A phenomenological study of the lived experience of long-term urinary catheterization (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database. (UMI No. 9941919)

Wilde, M.H. (1999b). Why embodiment now? Advances in Nursing Science, 22, 25–38. doi:10.1097/00012272-199912000-00004

About the Author(s)

Katherine E. Leonard, RN, MS, FNP-BC, is a nurse practitioner in the Department of Medicine/Oncology and Melanie A. Kalman, RN, PhD, is a professor, both at the State University of New York Upstate Medical University in Syracuse. No financial relationships to disclose. Mention of specific products and opinions related to those products do not indicate or imply endorsement by the Oncology Nursing Forum or the Oncology Nursing Society. Leonard can be reached at leonardk@upstate.edu, with copy to editor at ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted December 2014. Accepted for publication March 15, 2015.)