Great Plains American Indians’ Perspectives on Patient and Family Needs Throughout the Cancer Journey

Purpose: To explore the perspectives on patient and family needs during cancer treatment and survivorship of American Indian (AI) cancer survivors, caregivers, Tribal leaders, and healers.

Participants & Setting: 36 AI cancer survivors from three reservations in the Great Plains region.

Methodologic Approach: A community-based participatory research design was employed. Postcolonial Indigenous research techniques of talking circles and semistructured interviews were used to gather qualitative data. Data were analyzed using content analysis to identify themes.

Findings: The overarching theme of accompaniment was identified. The following themes were intertwined with this theme: (a) the need for home health care, with the subthemes of family support and symptom management; and (b) patient and family education.

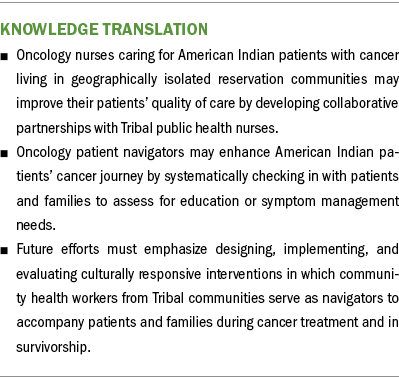

Implications for Nursing: To provide high-quality cancer care to AI patients in their home communities, oncology clinicians should collaborate with local care providers, relevant organizations, and the Indian Health Service to identify and develop essential services. Future efforts must emphasize culturally responsive interventions in which Tribal community health workers serve as navigators to accompany patients and families during treatment and in survivorship.

Jump to a section

High-quality cancer care is a continuum that includes prevention, detection, treatment, palliative care, and end-of-life care (Levit et al., 2013; Patel, Lopez, et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2017). In addition, high-quality cancer care is patient centered, evidence based, comprehensive, affordable, and accessible, and it is delivered by a highly trained team that coordinates with primary care providers and across other healthcare specialties (Levit et al., 2013). An infrastructure that supports high-speed internet for data collection and communication is integral to the delivery and monitoring of outcomes for high-quality cancer care. However, access to this level of care is lacking in rural and frontier regions of the United States because of a host of factors. These factors include fewer primary and specialty clinicians (e.g., oncology, surgery, palliative care), fewer cancer centers, and greater travel distance to access oncology care (Iglehart, 2018; Levit et al., 2020).

Background

Rural residents’ cancer burden is often exacerbated by personal and social factors, such as lower socioeconomic status, inadequate health insurance, fewer prevention and screening services, and mistrust of the healthcare system (Iglehart, 2018; Levit et al., 2020; National Cancer Institute, 2022; Patel, Lopez, et al., 2020). In rural areas of the Great Plains region, particularly in Tribal communities, the cancer burden disparities are even more significant (Rural Health Information Hub, 2019). When compared to White individuals, American Indian (AI) people living in the Great Plains experience higher incidence rates of breast, cervical, colorectal, and lung cancers, which are often diagnosed at more advanced stages and lead to considerably higher mortality rates (South Dakota Department of Health, 2019). In addition, AI patients, particularly those living in rural and frontier regions, are less likely to participate in cancer prevention and screening, may elect to forgo cancer surgery or receive oncology care after diagnosis, and may not use or have access to hospice and palliative care services (Guadagnolo et al., 2017; Jervis & Cox, 2019; Soltoff, Isaacson, et al., 2022).

AI Cancer Care Experience

Studies exploring AI patients’ cancer care experiences across various Tribal communities (i.e., Southwest, Oklahoma, and Pacific Northwest) identified similar themes. Many reported communication challenges among their families, communities, and clinicians, and between cancer centers and primary care teams. AI cancer survivors described feeling stigmatized by community members and having family conflicts about choosing either traditional or Western medicine (Craft et al., 2017; Hodge et al., 2020). Oncology clinicians expect their patients to ask questions and to report pain or other symptoms, but AI patients often remain quiet or stoic as a measure of respect and may not openly discuss cancer symptoms or treatment side effects because of cultural considerations (Burnette et al., 2019; Craft et al., 2017; Gachupin et al., 2019; Haozous et al., 2016; Hodge et al., 2020). Challenges with healthcare fragmentation emerged as a consistent theme throughout all the studies. Survivors and families described issues during transitions of care from oncology to home, primary care, or hospice care, with many family members assuming complete care at home with minimal support or training (Burnette et al., 2019; Craft et al., 2017; Gachupin et al., 2019; Haozous et al., 2016; Hodge et al., 2020).

Indian Health Service and Palliative Care

High-quality cancer care for people with advanced cancer includes palliative care (Smith et al., 2017). However, for individuals living in rural areas of the Great Plains, including Tribal communities, there are barriers to this specialty service. Reasons for these barriers include clinician and patient misconceptions, shortage of palliative care clinicians, limited palliative care knowledge in patients and clinicians, lack of infrastructure, and insufficient funding at Indian Health Service (IHS) facilities (Isaacson, 2017; Isaacson et al., 2015; Lalani & Cai, 2022; Soltoff, Isaacson, et al., 2022; Soltoff, Purvis, et al., 2022). For reservation-dwelling AI patients, primary healthcare services are often provided by the IHS, which is funded by the U.S. Congress through discretionary appropriations and is chronically underfunded (Lofthouse, 2022). Although treaty obligations guarantee health care for the enrolled members of the 574 federally recognized Tribes, this lack of funding severely limits the capacity of the IHS to offer specialty services like oncology or palliative care (National Indian Health Board, n.d.). Yet even with these barriers, Soltoff, Isaacson, et al. (2022) identified that the implementation and sustainability of palliative care programs within Tribal communities is possible if there is administrative support, a team of individuals to champion the cause, community engagement, and the incorporation of cultural values.

To address the disparities identified in rural cancer care specific to Great Plains Tribes, this study used an innovative collaboration consisting of three Tribal communities, a Tribal organization, regional academic and clinical programs focused on cancer disparities and palliative care, and a national partner committed to improving the health and health care of Tribes. The overarching goal of this collaborative study was to develop and test the delivery of a culturally responsive palliative care intervention for AI patients with cancer in the Great Plains. This article shares the results of a community needs assessment, in which the aims were to listen to and understand Tribal communities’ needs related to treatment and survivorship.

Methodologic Approach

As the first phase of a larger study, this study employed a community-based participatory research design (Elk et al., 2020; Israel et al., 2008, 2013; Wallerstein et al., 2020). The conceptual model for this research design was developed by Wallerstein et al. (2020) and contains the following four components: contexts (e.g., social-structural, collaboration, trust, mistrust), partnership processes (e.g., individual characteristics, relationships), intervention and research (e.g., integration of community knowledge, culture-centered interventions), and outcomes (e.g., intermediate, long-term). Community engagement and partnership are critical to this model, which began with the development of three community advisory boards (CABs). CAB members were recruited by individuals from the research team, whose years of prior work with the Tribes had established trusting, collaborative relationships. CAB members’ roles varied, but all were longtime residents of their Tribal communities. For example, CAB members included health administrators, counselors, teachers, homemakers, and a spiritual healer. Through quarterly meetings, each CAB shared in the development of interview questions, ideas on how to recruit participants, and participant selection processes. The Partners Human Research Institutional Review Board approved this project for human subject research. Tribal health committees, a Tribal research review board, and Great Plains IHS Institutional Review Board also approved this study.

Participants and Setting

Participant recruitment from three Tribal communities in the Great Plains occurred from November 2020 to May 2021. The following participant eligibility criteria were developed after receiving input from the CABs: (a) being aged 21 years or older, (b) self-identifying as AI individuals, and (c) residing at least part-time in one of three designated reservations. As experts in their Tribal communities, the CABs based these criteria on anticipating greater maturity at age 21 years, understanding the frustration among Tribal members when asked to verify Tribal identity, and knowing that Tribal members often need to move from or back to the reservation for a variety of reasons. The researchers then developed inclusion criteria specific to each of the following groups of participants in this study: (a) cancer survivors—having a cancer diagnosis other than skin cancer; (b) caregivers—being identified by a cancer survivor as providing physical, mental, emotional, or spiritual support and having cared for someone in the past five years; (c) Tribal leaders—being identified by CAB members; and (d) Tribal healers—being identified by CAB members. Participants were excluded if they were unable to provide informed consent. The sample size was based on CAB feedback and the study’s exploratory nature. The following samples were sought from each Tribal community: (a) cancer survivors (n = 7), (b) caregivers (n = 6), (c) Tribal leaders (n = 2), and (d) Tribal healers (n = 2).

Recruitment

This study employed purposive sampling techniques to recruit participants. CAB members actively identified and contacted potential participants. If they expressed interest, CAB members shared their contact information with a research team member, who then began the informed consent process. The research team also used snowball sampling techniques, which consisted of asking participants to contact individuals they felt might be interested and who met the inclusion criteria (Kirchherr & Charles, 2018), after each interview and talking circle.

Talking Circles and Interviews

A talking circle is a postcolonial Indigenous research technique that emphasizes “relational ways of knowing” (Chilisa, 2020a, p. 251). Talking circles employ active listening and storytelling, where, through collective sharing, all gain understanding (Hunt & Young, 2021). During talking circles, participants may ask questions between and among themselves and the researcher. This openness creates an environment of trust, builds relationships, and promotes the collective and collaborative generation of knowledge (Chilisa, 2020a, 2020b).

Following recommendations from the CABs, cancer survivors participated in two talking circles. The first provided an opportunity for them to share their unique experience of cancer, and the second provided an opportunity to respond to specific questions about their needs while receiving cancer care. Caregivers participated in one talking circle, which used a talking circle guide like that used with cancer survivors. The goal was to obtain an equal, or as close to equal as possible, number of participants from each reservation as possible for the talking circles. Talking circles were conducted until similar stories and themes emerged across the survivor and caregiver groups (thematic saturation) in comparatively equal numbers from each Tribal community. Talking circles lasted roughly two hours.

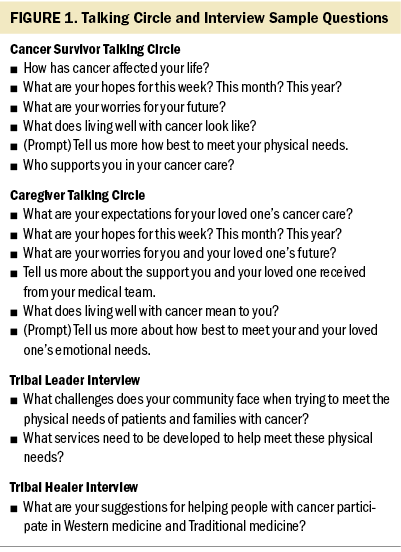

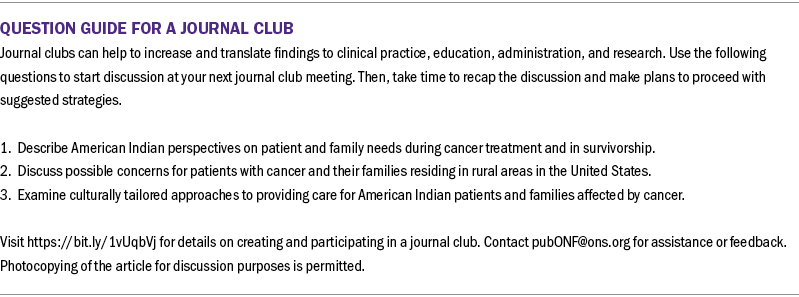

Following recommendations from the CABs, the researchers completed individual interviews with Tribal leaders and healers. An adapted interview guide from the second talking circle was used with the leaders, and the CABs designed an interview guide for the healers. The interviews lasted 30–60 minutes. See Figure 1 for examples of questions from the talking circle and interview guides. Questions were broad enough to allow each participant’s story to unfold and did not specifically ask about any of the themes that emerged.

Data Collection

In light of COVID-19, the Tribal health boards advised that videoconferencing be used rather than face-to-face interviews. Three research team members, two AI and one White, led the talking circles and interviews. All the talking circles and leader interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by a trained transcriptionist. Following CAB recommendations, the interview team took extensive handwritten notes during the healer interviews and combined them into a synthesized narrative.

Data Analysis

Following Elo and Kyngäs’s (2008) technique, an experienced qualitative researcher provided training in content analysis and then guided the data analysis team in coding and categorizing the narratives. Comprising the team were two palliative care specialists, two research associates, and two public health professionals. The team was then divided into three groups consisting of one AI research team member and one White research team member, with each person’s background contributing to the analytic process. For example, the AI team members provided cultural context and understanding, and the palliative care members reviewed the narratives from a medical perspective. The three groups began with assignments to review the transcripts for the survivor talking circles, caregiver talking circles, leader interviews, and healer interviews. The following steps were taken to ensure rigor in the analytic process: (a) Each member independently read and coded their assigned transcripts assisted by NVivo Pro, version 12.0; (b) team meetings were held to discuss initial codes and categories and identify similar codes and categories across all the transcripts; and (c) a codebook was created for all team members to assist with independent coding of the transcripts that they had not previously analyzed. If members identified codes not previously noted in the codebook, they added new codes and attached supporting participant narratives. After all members had coded all the transcripts, the team met again, openly discussed their codes and categories, and combined similar codes into categories until they reached consensus. Three team members then synthesized the narrative data supporting the final categories, which then became the final themes. These themes, along with supporting narrative data, were presented to the three CABs for their assessment and feedback. CAB members expressed that the identified themes were very relevant to their communities, with members sharing personal stories of family members who had experienced challenges like those expressed during the talking circles and interviews.

Findings

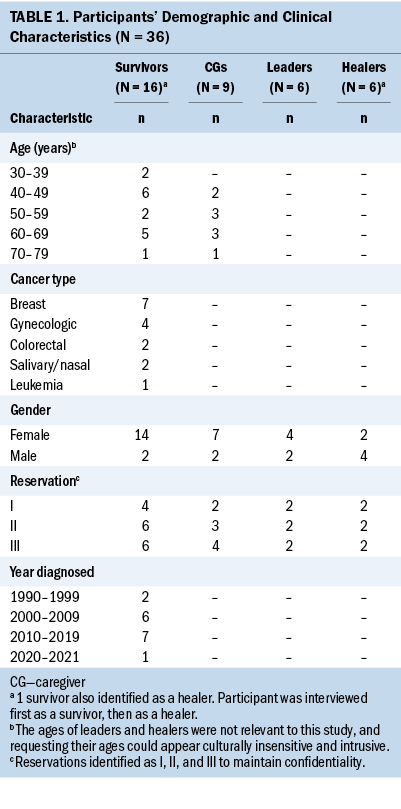

Thirty-six AI participants shared their experiences of what patients and families need during treatment and in survivorship. Tribal research and health boards requested that only essential demographic data needed for this assessment be obtained. For cancer survivors, age, cancer type, and year diagnosed were collected, and only age was collected for caregivers. The three reservation communities were equally represented across all groups (see Table 1). The overarching theme of accompaniment was identified by content analysis. The following themes were intertwined with this overarching theme: (a) the need for home health care, with the subthemes of family support and symptom management; and (b) patient and family education.

Accompaniment

Across all narratives, the overarching theme was that for patients and caregivers to live well with cancer, they need accompaniment. Accompaniment is defined as being present with a patient and their caregivers for as long as needed throughout their cancer journey. Tribal leaders indicated a high need for navigation services like those at cancer centers but situated within the reservation and delivered by Tribal members. Accompaniment in Tribal communities could be delivered by an AI community health worker (CHW), who resides in and is a member of the community. This CHW could provide education, companionship, and advocacy for AI patients throughout the continuum of the cancer experience. The Tribal navigator or CHW would ideally provide education about the cancer diagnosis including trajectory, assist with accessing social services, connect patients and caregivers to spiritual healers and resources as well as lay mental health counseling, and work as a liaison with cancer centers. Cancer survivors shared how their cancer center navigators were universally beloved, and survivors who received these navigation services found them to be beneficial, informative, and supportive of their cancer care and treatment. A survivor stated the following:

[My cancer center navigator] was awesome. As soon as I went there, she came and found me. And she told me, 'I’m here for you. If you need anything, you come see me.' And they gave me money to buy a wig and just all kinds of [assistance]; she was just awesome. I could go talk to her any time I needed to, and I did a lot.

Tribal leaders indicated how useful navigators could be within their communities as local points of contact to accompany patients and families on their cancer journey, while also providing employment opportunities for community members. One Tribal leader stated,

I think that navigation service is highly needed here as well, could be hugely beneficial, and doesn’t require a doctor, you know. It would be local, providing jobs for local people, entry-level jobs for local people who are from here, who know the people.

Another Tribal leader identified how the navigator could work similarly to a case manager or home healthcare services, stating the following:

Navigation [is an important service] because that person could help them manage that situation, right? Help them access whatever thing that they were needing. . . . Those people could be mobile. They could be providing the home health [care]. They could be providing that home assessment also. They could be doing so much, not just, you know, navigating.

Although Tribal leaders identified how navigators could assist patients and families experiencing cancer with accessing services, the perspectives of cancer survivors and caregivers emphasized the importance of human connection or accompaniment. A survivor shared the following:

Sometimes it might be a cookie, sometimes it might be a meal, sometimes it might be coffee, sometimes it might be, “I’m just going to sit with you today, I’ll sit with you and hold your hand, you don’t have to say anything, you can just be there.”

Another survivor stated,

What I desire mostly is having some kind of companionship, you know, when you can’t sleep at night, when you’re up at 3 or 4 [o’clock] . . . [when] you’re up hurting or you’re having a hard time in your mind with all the really heavy-duty stuff that you deal with.

Need for Home Health Care

The need for home health care was also a major theme and contained the subthemes of family support and symptom management. Caregivers, cancer survivors, and Tribal leaders identified the urgent need for home healthcare services within reservation boundaries. A survivor described how her daughter took on a medical role in the home to provide such care:

When I had my mastectomy, and I had two tubes, drainage tubes coming out, and they had to be measured and, I mean, to me it was just really gross. . . . They would drain them in the morning and night. . . . My daughter did that.

Participants also commented on the difficulties obtaining durable medical equipment, such as oxygen, hospital beds, and wheelchairs, saying, “The oxygen, it was kind of a hassle to get help with that, to get her a portable machine,” “[I] bought a bed for him,” and “[A local agency] . . . helped my mom with the wheelchair because it got to the point where she couldn’t walk.”

Although participants identified home health care as an urgent need, they also recognized that if a program was started, it might not be readily accepted by the community. Reasons for this varied, with participants indicating how resourceful and independent Native families are because they are unaccustomed to having access to abundant resources. One survivor stated the following:

We as Natives, we don’t ask for help, you know. That’s a very difficult process for us, but to ask for help when you’ve got nobody in the house but you, you know, to reach out and say, “I need help, I need help doing this.”

Family Support

AI cancer survivors, caregivers, and Tribal leaders identified the need for increased family support when patients are seriously ill. Participants described the challenges families faced when caring for their loved ones, including physical care. The theme of family support encompasses support needed for patients with cancer from their family and support needed for the patient’s family itself. These two elements relate to the Lakota concepts of tiwahe and tiospaye. As one survivor mentioned,

Cancer is not an individual disease. Cancer is a family disease. And no matter how many people or . . . how few people you have in your family, they’re all affected by it. . . . My kids are in California, but they’ve been affected by it. And my family on the reservation, they’ve been affected by it.

Family support was needed for physical care. Families often end up providing makeshift home health care for their loved one, because visiting nurses or patient care attendants in the home are not common. A survivor described the following:

Living well with cancer does not work when you’re dealing with IHS and you live on the reservation. It doesn’t work because there’s no facilities. There’s nothing. . . . And if you don’t have a real strong family support behind you, you’re in trouble, because otherwise there’s nothing out there.

Another caregiver mentioned the following about how helpful it would be to have someone able to explain things to the family and to support them directly:

To answer questions for families, to take time and help them understand what’s happening to somebody, the person that they love. . . . Even as a nurse, I didn’t absorb a lot of the information that was being said to me. And so the need to be able to support those people that are your supporters would really be important and helpful.

Similarly, caregiver strain, in the form of emotional strain and practical or logistical strain, was identified. A caregiver shared the following:

The employment here [on the reservation] isn’t very well organized, so people with serious illnesses and stuff, it causes havoc in a family because either you’re going to get fired or, you know, you’re going to lose time off at work, you know . . . something that’s kind of hard to do for them.

A Tribal leader expressed, “We have a lot of family members that just take [the patient] home, but then they tend to panic, or they realize how much work it’s going to be, and then the patient ends up [in the hospital].”

Participants also described that even with strong family support, it was important to have people who were outside the family to speak with for support. A caregiver stated,

I think, like this, what we’re doing right now [the talking circle], being able to talk about it to someone that we don’t know because sometimes it’s not easy for someone to open up to a family member. Sometimes it’s easier for them to open up to a person they don’t even know.

Symptom Management

Cancer survivors and caregivers shared difficult experiences managing symptoms from cancer treatment while living within their rural Tribal community. Managing symptoms included trying to help keep pain and/or nausea under control, and there were challenges with accessing medications needed to treat these symptoms. Family members had to play the role of nurse or nurse’s aide. A caregiver expressed how helpful it would have been to have help, stating the following:

Someone coming out to the house because with my mom, she needed her stuff, her vitals and stuff, checked constantly, and we didn’t have the equipment for that. And IHS doesn’t provide that service that I know of, to come out to the home to do that.

Although unchecked physical pain was not common among the participants in this study, survivors and caregivers mentioned lethargy, fatigue, wound care difficulties, and hair loss as common physical health concerns that resulted from their cancer treatment. One participant said, “And, I mean, like my [chemotherapy sessions] were like eight hours long, and it was every three weeks. And by the time you went through, like maybe the first two weeks were like hell trying to get bounced back.”

In addition, caregivers were often responsible for the prescription medication for the loved one with cancer. Because of IHS policies and procedures, photo identification is required for receiving medication from their pharmacy, and this was frustrating to some participants. A caregiver shared the following example of her experience:

Yeah, there was a lot of frustration because [of] medicines and, see, one of the requirements that they had here [was], you had to go there to get the narcotics yourself because you had to produce an ID. And the other thing is, there were a lot of times where they did not have those kind of medicines if they had to be ordered, which was even more frustrating.

Patient and Family Education

Across all sites, talking circles, and interview groups, participants shared the importance of person- and family-centered education specific to the cancer illness trajectory. They identified it as crucial that patients with cancer and their families understand and be able to deal with the side effects of chemotherapy and be prepared for what happens when treatment is completed. Several participants indicated that patients with cancer and their families are often uncertain about speaking up and are not used to asking questions or questioning someone who appears to be an authority, stating, “Us Natives, we don’t really ask a lot of questions even though we have them, particularly when there’s a large crowd.” One caregiver explained that the first treatment went very well, so they anticipated that all treatments would proceed similarly. However, this was not the case, which she described as follows:

The next treatment she slept, I think, for 18 hours, and she just could not get out of bed. . . . The symptoms were so crazy. She had a lot of joint pain, like her, the insides of her fingers would burn and sting. . . . I think her fingernails turned black. . . . I just didn’t have any idea. . . . So all of it was just completely not anything like I expected.

Tribal leaders and healers’ views on education were similar to those of cancer survivors and caregivers, adding the critical need for the education to be simple and in layman’s terms. A healer said, “I always tell people that we need to talk to our patients like they’re in second grade. Not because they’re stupid, but because they don’t understand the medical terms that we use.”

Paradoxically, although having someone come to the home would be helpful, participants also noted how difficult it is to ask for help or even openly share their diagnosis. Native families living in rural reservation communities have learned to be self-reliant and resourceful. One participant said, “I’m not used to asking for help or people helping me. . . . It’s tough to accept.” Another survivor stated, “I didn’t want anybody to know because I didn’t want nobody to be sad for me.”

Discussion

Although these findings are specific to three Tribal reservations in the Great Plains and not generalizable to other Tribal communities, they provide crucial information for oncology practices serving Tribal communities to consider. The participants shared that because of the lack of home healthcare services, families often take on the burden of providing medical care at home. Gachupin et al. (2019) also identified family concerns regarding the lack of preparation they had been given when assuming the role of primary care clinician in the home setting. Not only do caregivers need education and support in providing physical care, but they also need social support as they journey with their loved one experiencing cancer. The roles that family caregivers play in the social, emotional, and physical care for their family members create a great deal of strain, and they need respite. A study by Haozous et al. (2016) involving AI and Alaska Native participants in the Pacific Northwest also identified caregiver fatigue as a concern. However, unlike the current study, their participants identified the value of a homecare nurse in offsetting the burden of care (Haozous et al., 2016).

In addition, some narratives illustrated the challenges patients with cancer and their families experience when trying to obtain the needed medications to manage symptoms appropriately. This becomes particularly difficult when the oncologist orders a medication that is unavailable through IHS. Caregivers are then tasked with contacting the oncology clinician for a different medication, which may delay treatment and add to the patient’s symptom burden. It is critical that oncology practices serving reservation-dwelling AI patients be in contact with the IHS pharmacy to ensure that medications they order are obtainable (Dwyer et al., 2022).

Participants also described the critical need for navigation services in reservation communities. Although navigation services may be provided by existing Tribal CHW services, they were not available for the participants in this study. In addition, cancer center navigators are often two to five hours from where patients and families receive oncology care, making communication and service delivery challenging. Previous studies have also identified communication challenges, including AI reluctance to report symptoms, delayed information sharing from oncology to primary care, and a lack of a central point of contact within the Tribal community (Craft et al., 2017; Dwyer et al., 2022; Gachupin et al., 2019; Haozous et al., 2016).

These communication challenges could be addressed if AI navigators, who were also individuals from the same community as the patient, could coordinate care by linking patients and families with services in the community and with their oncology clinicians. The need for human connection, caring, and accompaniment is great. As one survivor stated, “And just being there [with the person] and talking a lot of times is the most important thing.” This quote demonstrates the paramount importance of accompaniment, where someone accompanying the patient and their caregivers on their cancer journey can be a listening ear, help them to access services, and assist them with asking questions of their clinicians to better understand their cancer care. This reflects findings from a study by Bastian and Burhansstipanov (2020) in which AI cancer survivors identified the importance of advocacy and having another person attend doctor visits to help patients understand their plan of care. Participants in the study stressed how important it was for them to understand their cancer; this knowledge helped them become more adept at advocating for themselves (Bastian & Burhansstipanov, 2020).

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The participants were members of one Oyate or people, yet the three reservations represented in this sample consisted of six differing bands from this Oyate, so these findings may not be generalizable to other Tribal communities. In addition, the team conducting the qualitative analysis consisted of three individuals new to the narrative data analysis process. The research team ensured rigor by providing hands-on education from the lead qualitative researcher and by pairing newer members with experienced qualitative researchers during the analysis. Although these individuals were less experienced in qualitative research methods, they brought a lifetime of experience to the analytic process as AI team members from the same Oyate.

Implications for Nursing

It is critical that oncology practices serving AI patients residing in reservation communities (a) are aware of what services (e.g., home health care) are available; (b) are in contact with the IHS pharmacy to ensure that medications ordered are obtainable; (c) provide verbal and written instructions to the patient and family; and (d) develop a check-in system with the patient and family once they have returned home to assess any potential concerns. AI patients, families, IHS, other Tribal health facilities, and oncology clinicians all identify communication and coordination as key challenges in providing high-quality cancer care to AI patients living in remote areas (Dwyer et al., 2022; Soltoff, Purvis, et al., 2022). Oncology clinicians may wish to create partnerships with IHS and Tribal health facilities to identify and collaboratively develop the essential services needed for patients with cancer and their families to live well in their home communities.

Conclusion

Access to high-quality cancer care is severely limited for AI patients with cancer and their families living in geographically isolated Tribal communities. These patients and families must travel great distances to receive care and, when returning to their home communities, experience greater cancer burden. This is often because of IHS service limitations, poor care coordination, and communication challenges between clinicians, patients, and families. Evidence for addressing these challenges is now emerging (Bastian & Burhansstipanov, 2020; Dwyer et al., 2022; Haozous et al., 2016), so it is crucial that oncology clinicians seek innovative ways to work collaboratively with IHS, Tribal healthcare services, and palliative care teams to ease AI patients’ cancer burden.

Evidence exists about the added value that a navigator can bring to oncology settings, such as decreased time from diagnosis to treatment, particularly in underserved populations (Bush et al., 2018). In addition, the body of evidence is growing regarding the benefits of lay health workers in easing symptom burden for cancer survivors (Patel, Ramirez, et al., 2020), and the role of the CHW in Tribal communities is well established (Rural Health Information Hub, 2020). Opportunities are present for oncology clinicians, IHS, and Tribal healthcare services to explore the training and employment of Tribal CHWs as navigators to bridge the communication and service gaps identified by patients with cancer and their families. Future efforts must focus on designing, implementing, and evaluating culturally responsive interventions using Tribal CHWs as navigators to accompany patients and families on their cancer journey.

About the Authors

Mary J. Isaacson, PhD, RN, CHPN®, is an associate professor in the College of Nursing at South Dakota State University in Rapid City; Tinka Duran, MPH, is a senior director and Gina R. Johnson, BSc, is a program manager, both at the Great Plains Tribal Leaders Health Board in Rapid City, SD; Alexander Soltoff, BS, is a PhD student in the department of Health Policy and Management at Emory University in Atlanta, GA; Sean M. Jackson, MPH, is an evaluation unit manager and lead evaluator at the Great Plains Tribal Leaders Health Board; Sara J. Purvis, MPH, is a research project coordinator at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston; Michele Sargent, RN, is a program manager and J.R. LaPlante, JD, is the director of tribal relations and health services, both at Avera Health in Rapid City, SD; Daniel G. Petereit, MD, FABS, FASTRO, is a radiation oncologist in the Dakota West Radiation Oncology Cancer Care Institute at Monument Health in Rapid City, SD; Katrina Armstrong, MD, is the dean of the Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University in New York, NY; and Bethany-Rose Daubman, MD, is the codirector of the global palliative care program in the Division of Palliative Care and Geriatrics at Massachusetts General Hospital. This research was supported, in part, by the Improving the Reach and Quality of Cancer Care in Rural Populations grant from the National Cancer Institute (1R01CA240080-01) and by a grant from the Cambia Health Foundation. Daubman has received funding from the Cambia Health Foundation as part of the Sojourns Scholar Leadership Program. Isaacson, Duran, Sargent, LaPlante, Petereit, Armstrong, and Daubman contributed to the conceptualization and design. Isaacson, Duran, Johnson, and Daubman completed the data collection. Daubman provided statistical support. Isaacson, Duran, Johnson, Soltoff, Jackson, Purvis, Sargent, Petereit, and Daubman provided the analysis. Isaacson, Soltoff, and Daubman contributed to the manuscript preparation. Isaacson can be reached at mary.isaacson@sdstate.edu, with copy to editor at ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted August 2022. Accepted December 9, 2022.)

References

Bastian, T.D., & Burhansstipanov, L. (2020). Sharing wisdom, sharing hope: Strategies used by Native American cancer survivors to restore quality of life. JCO Global Oncology, 6, 161–166. https://doi.org/10.1200/jgo.19.00215

Burnette, C.E., Roh, S., Liddell, J., & Lee, Y.-S. (2019). American Indian women cancer survivor’s needs and preferences: Community support for cancer experiences. Journal of Cancer Education, 34(3), 592–599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-018-1346-4

Bush, M.L., Kaufman, M.R., & Shackleford, T. (2018). Adherence in the cancer care setting: A systematic review of patient navigation to traverse barriers. Journal of Cancer Education, 33(6), 1222–1229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-017-1235-2

Chilisa, B. (2020a). Decolonizing the interview method. In B. Chilisa (Ed.), Indigenous research methodologies (2nd ed., pp. 248–266). Sage.

Chilisa, B. (2020b). Indigenous mixed methods in program evaluation. In B. Chilisa (Ed.), Indigenous research methodologies (2nd ed., pp. 169–185). Sage.

Craft, M., Patchell, B., Friedman, J., Stephens, L., & Dwyer, K. (2017). The experience of cancer in American Indians living in Oklahoma. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 28(3), 259–268. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659616634169

Dwyer, K., Anderson, A., Doescher, M., Campbell, J., Wharton, B., & Nagykaldi, Z. (2022). Provider communication: The key to care coordination between tribal primary care and community oncology providers. Oncology Nursing Forum, 49(1), 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1188/22.ONF.21-35

Elk, R., Emanuel, L., Hauser, J., Bakitas, M., & Levkoff, S. (2020). Developing and testing the feasibility of a culturally based tele-palliative care consult based on the cultural values and preferences of Southern, rural African American and White community members: A program by and for the community. Health Equity, 4(1), 52–83. https://doi.org/10.1089/heq.2019.0120

Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

Gachupin, F.C., Garcia, C.A., & Romero, M.D. (2019). An American Indian patient experience. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 30(4, Suppl.), 62–65. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2019.0116

Guadagnolo, B.A., Petereit, D.G., & Coleman, C.N. (2017). Cancer care access and outcomes for American Indian populations in the United States: Challenges and models for progress. Seminars in Radiation Oncology, 27(2), 143–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semradonc.2016.11.006

Haozous, E.A., Doorenbos, A., Alvord, L.A., Flum, D.R., & Morris, A.M. (2016). Cancer journey for American Indians and Alaska Natives in the Pacific Northwest. Oncology Nursing Forum, 43(5), 625–635. https://doi.org/10.1188/16.ONF.625-635

Hodge, F.S., Itty, T.L., Samuel-Nakamura, C., & Cadogan, M. (2020). We don’t talk about it: Cancer pain and American Indian survivors. Cancers, 12(7), 1932. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12071932

Hunt, S.C., & Young, N.L. (2021). Blending Indigenous sharing circle and Western focus group methodologies for the study of Indigenous children’s health: A systematic review. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069211015112

Iglehart, J.K. (2018). The challenging quest to improve rural health care. New England Journal of Medicine, 378(5), 473–479. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMhpr1707176

Isaacson, M.J. (2017). Wakanki ewastepikte: An advance directive education project with American Indian elders. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing, 19(6), 580–587. https://doi.org/10.1097/NJH.0000000000000392

Isaacson, M.J., Karel, B., Varilek, B.M., Steenstra, W.J., Tanis-Heyenga, J.P., & Wagner, A. (2015). Insights from health care professionals regarding palliative care options on South Dakota reservations. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 26(5), 473–479. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659614527623

Israel, B.A., Eng, E., Schulz, A.J., & Parker, E.A. (2013). Introduction to methods for CBPR for health. In B.A. Israel, E. Eng, A.J. Schulz, & E.A. Parker (Eds.), Methods for community-based participatory research for health (2nd ed., pp. 3–39). Jossey-Bass.

Israel, B.A., Schulz, A.J., Parker, E.A., Becker, A.B., Allen, A.J., III, & Guzman, R. (2008). Critical issues in developing and following CBPR principles. In M. Minkler & N. Wallerstein (Eds.), Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes (2nd ed., pp. 48–66). Jossey-Bass.

Jervis, L.L., & Cox, D.W. (2019). End-of-life services in tribal communities. Innovation in Aging, 3(Suppl. 1), S667–S668. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igz038.2469

Kirchherr, J., & Charles, K. (2018). Enhancing the sample diversity of snowball samples: Recommendations from a research project on anti-dam movements in Southeast Asia. PLOS ONE, 13(8), e0201710. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201710

Lalani, N., & Cai, Y. (2022). Palliative care for rural growth and wellbeing: Identifying perceived barriers and facilitators in access to palliative care in rural Indiana, USA. BMC Palliative Care, 21(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-022-00913-8

Levit, L.A., Balogh, E., Nass, S., & Ganz, P.A., (Eds.). (2013). Delivering high-quality cancer care: Charting a new course for a system in crisis. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/18359

Levit, L.A., Byatt, L., Lyss, A.P., Paskett, E.D., Levit, K., Kirkwood, K., . . . Schilsky, R.L. (2020). Closing the rural cancer care gap: Three institutional approaches. JCO Oncology Practice, 16(7), 422–430. https://doi.org/10.1200/op.20.00174

Lofthouse, J. (2022). Increasing funding for the Indian Health Service to improve Native American health outcomes. Mercatus Center at George Mason University. https://www.mercatus.org/publications/healthcare/increasing-funding-ind…

National Cancer Institute. (2022, May 5). Rural cancer control. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/hdhe/research-emphasis/rural-cancer-co…

National Indian Health Board. (n.d.). Indian health 101. https://www.nihb.org/tribal_resources/indian_health_101.php

Patel, M.I., Lopez, A.M., Blackstock, W., Reeder-Hayes, K., Moushey, E.A., Phillips, J., & Tap, W. (2020). Cancer disparities and health equity: A policy statement from the American Society of Clinical Oncology. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 38(29), 3439–3448. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.20.00642

Patel, M.I., Ramirez, D., Agajanian, R., Agajanian, H., & Coker, T. (2020). Association of a lay health worker intervention with symptom burden, survival, health care use, and total costs among medicare enrollees with cancer. JAMA Network Open, 3(3), e201023. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.1023

Rural Health Information Hub. (2019, April 22). Rural health disparities. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/rural-health-disparities

Rural Health Information Hub. (2020, September 8). Community health workers in Tribal communities. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/toolkits/community-health-workers/4/ada…

Smith, C.B., Phillips, T., & Smith, T.J. (2017). Using the new ASCO clinical practice guideline for palliative care concurrent with oncology care using the TEAM approach. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book, 37, 714–723. https://doi.org/10.1200/edbk_175474

Soltoff, A.E., Isaacson, M.J., Stoltenberg, M., Duran, T., LaPlante, L.J.R., Petereit, D., . . . Daubman, B.-R. (2022). Utilizing the consolidated framework for implementation research to explore palliative care program implementation for American Indian and Alaska Natives throughout the United States. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 25(4), 643–649. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2021.0451

Soltoff, A., Purvis, S., Ravicz, M., Isaacson, M.J., Duran, T., Johnson, G., . . . Daubman, B.-R. (2022). Factors influencing palliative care access and delivery for Great Plains American Indians. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 64(3), 276–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2022.05.011

South Dakota Department of Health. (2019). South Dakota American Indian cancer disparities data report. https://getscreened.sd.gov/documents/AmericanIndianCancerDisparitiesRep…

Wallerstein, N., Oetzel, J.G., Sanchez-Youngman, S., Boursaw, B., Dickson, E., Kastelic, S., . . . Duran, B. (2020). Engage for equity: A long-term study of community-based participatory research and community-engaged research practices and outcomes. Health Education and Behavior, 47(3), 380–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198119897075