Struggling, Adapting, and Holding Each Other Up: A Qualitative Study of Oncology Nurses During the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Purpose: To explore the experience of oncology nurses during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Participants & Setting: 21 RNs, advanced practice RNs, and physician associates from inpatient and ambulatory care settings at a comprehensive cancer center in the northeastern United States.

Methodologic Approach: A qualitative study using interpretive description was conducted through semistructured interviews. Data were recorded and transcribed verbatim, reviewed for accuracy, and coded into themes following an iterative process of analysis.

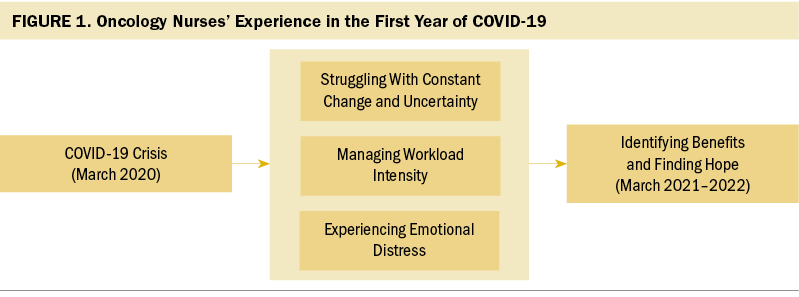

Findings: The theme of “Doing It Together: Struggling, Adapting, and Holding Each Other Up” describes the experience of oncology nurses during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. The following three themes provide further insight: “Struggling With Constant Change and Uncertainty,” “Managing Workload Intensity,” and “Experiencing Emotional Distress.” As the year progressed, “Identifying Benefits and Finding Hope” began to emerge.

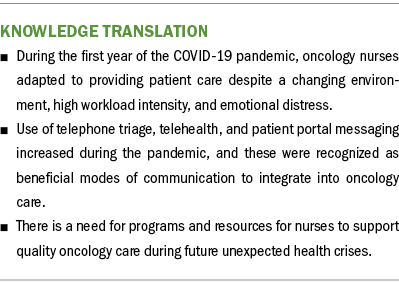

Implications for Nursing: The findings suggest a need for programs to help nurses cope with the continuing effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, mental health and well-being resources, and nursing guidelines for telehealth and relocation to other units.

Jump to a section

The COVID-19 pandemic has created a global and domestic healthcare crisis. In particular, the field of oncology faced unique challenges and risks associated with an immunosuppressed population of patients (Sullivan et al., 2020), including transition to telehealth for routine care visits (Indini et al., 2020), interruption of treatment, and barriers to delivering palliative care (Pahuja & Wojcikewych, 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically increased nurse workload and strained healthcare delivery systems with high patient volumes and high-acuity hospitalized patients (Indini et al., 2020; Phillips et al., 2021; Schwerdtle et al., 2020). Workflow changes were required in ambulatory oncology care, and strategies were needed to balance screening symptomatic and asymptomatic patients with meeting the needs for urgent cancer treatment (Mayor, 2020; Paterson, Gobel, et al., 2020; Yackzan & Shah, 2021). Hospital units became COVID-19 units, and nurses were assigned new roles such as sourcing personal protective equipment, evaluating surge capacity, and implementing safety guidelines for staff and patients with and without COVID-19 (Cortiula et al., 2020; Treston, 2020).

In addition, many non-nursing staff and physicians worked remotely, leading to increased responsibilities for nurses (Galanis et al., 2021). Telehealth developed rapidly for a wide range of nursing responsibilities, which created challenges for communication and continuity of care (Elkin et al., 2021; Paterson, Bacon, et al., 2020; Zon et al., 2021). However, there is a need to understand the experience of nurses to develop system-level strategies to improve work environments for present and future challenges (Lyon, 2022).

Some oncology units on the main campus of the study institution became COVID-19 units, which pushed the oncology units to other settings. The COVID-19 pandemic also prompted relocation of many ambulatory oncology services and nursing staff from the hospital’s main campus to other sites across the network. Perspectives of physicians during the pandemic have been described (Castelletti, 2020; Parsons Leigh et al., 2021), but there are few examples of the experience of nurses during the first year of the pandemic in the United States (Cacchione, 2020; Schwerdtle et al., 2020; Treston, 2020). The purpose of this exploratory study was to describe the experiences of oncology nurses related to work environment, workload, and psychological responses during the first year of the pandemic, as well as to gain insight from nurses about patients and families.

Methods

Qualitative inquiry is a methodologic approach to explore an experience or phenomenon for which little is known (Creswell & Poth, 2017). Traditional qualitative methods grounded in other disciplines have limited applications to nursing and clinical phenomena (Thorne et al., 2016). Interpretive description is a pragmatic qualitative method that goes beyond generic description and integrates professional nursing knowledge to critically reflect on what is clinically meaningful (Thorne, 2016; Thorne et al., 2016). The study was approved by the Yale University Institutional Review Board with verbal participant consent. RNs and advanced practice RNs (APRNs) were recruited from the Smilow Cancer Hospital network, part of a National Cancer Institute–designated cancer center. Flyers and announcements at unit and manager meetings were the primary recruitment strategies.

Semistructured interviews were conducted from November 2020 through February 2021 to collect data. Participants were asked to reflect on their experience as oncology nurses since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020. Reflection is a methodologically sound approach to address experiences that occur during a defined timeline (Jairath et al., 2021). Interviews were conducted by Zoom videoconferencing, then recorded and transcribed verbatim by a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act–compliant transcription service. Demographic surveys were sent electronically using REDCap, a secure web application for building and managing survey data for research (Harris et al., 2009, 2019). Embedded at the end of the survey was the following statement: “I agree to allow the researchers of Yale School of Nursing participating in this project to use the anonymous information provided by me in this survey for the purposes of the study on the experience of oncology nurses during the COVID-19 crisis.” Two researchers independently read transcripts for accuracy, identified initial codes, and moved through the iterative process of coding, synthesis, and interpretation (Miles et al., 2019; Saldaña, 2016; Thorne, 2016). Codes were compared until consensus was reached, and analysis continued to determine themes. By interview 21, there was no new information, indicating saturation of data. A detailed draft of the codes, themes, and potential relationships among the themes was shared with the members of the research team for their insights, discussion, and conclusions. The Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research were reviewed by team members to prepare the analytic findings for publication (O’Brien et al., 2014).

Results

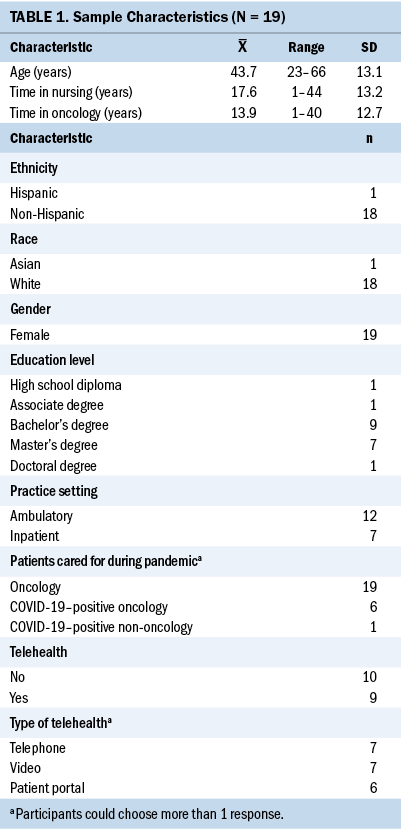

The sample consisted of 19 oncology nurses (16 RNs and 3 APRNs) and two physician associates. Demographic data were collected for only 19 participants because 2 did not complete the survey. Participants ranged in age from 23 to 66 years, 17 participants had a bachelor’s degree or higher, and time working in oncology ranged from 1 to 40 years. Seven participants worked on inpatient units, and 12 were in ambulatory practice. (see Table 1).

The experience of oncology nurses during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic was captured with the overarching theme “Doing It Together: Struggling, Adapting, and Holding Each Other Up.” The experience was explained using the interrelated themes of “Struggling With Constant Change and Uncertainty,” “Managing Workload Intensity,” and “Experiencing Emotional Distress” (see Figure 1). As the year progressed, “Identifying Benefits and Finding Hope” began to emerge.

Doing It Together: Struggling, Adapting, and Holding Each Other Up

Nurses demonstrated adaptability, creativity, teamwork, and dedication in caring for patients with cancer and their families, despite the challenges brought on by the pandemic, as shown by the following quotes:

- “We had to hold each other up. We did it. We always helped each other through.”

- “I would not have gotten through the pandemic without the teamwork of my peers.”

- “Everyone continued to put their best foot forward and function well for the patient as a team.”

- “Everybody just came together and focused on patient-centered care, which obviously is our number one priority.”

Struggling With Constant Change and Uncertainty

Early in the pandemic, practice settings and nursing roles were altered to meet changing needs. There was a sense of chaos because guidelines were constantly being revised as new information emerged, as shown in the following quotes:

- “I would say it’s been chaotic . . . at first a lot of unknowns, we didn’t know what to expect.”

- “Frustrated with constant changes, bombardment of emails, different policies rolled out and changed.”

Unit relocation and reassignment were associated with uncertainty, unpredictability, and distress. Some nurses were relocated with their teams and units, but others were reassigned as a result of census decreases because of delays in cancer treatment. Staffing needs were greater in critical care areas including COVID-19 care units. Deployment of oncology nurses to COVID-19 care units was very short-lived because the hospital had guidelines in place within six weeks that reflected the Oncology Nursing Society (2022) Recommendations for Oncology Staff Assignments During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nurses described the experience of uncertainty as follows:

- “Probably once or twice a week we were floated to another floor . . . sometimes up to the COVID-19 unit.”

- “Fear of the unknown. When you come in, you have no control over any of it . . . where they are going to send you . . . you could float to any unit. We’d find out in morning when we came in.”

For oncology nurses whose ambulatory clinical settings changed from hospital-based locations with acute care resources to community care centers that relied solely on calling 911 to manage emergencies, the adjustment was frustrating and challenging. Lack of usual resources, management of acute reactions, rapidly deteriorating patient conditions, and response times of emergency personnel to 911 calls resulted in a high level of distress, expressed in the following quotes:

- “Challenges from going from a clinic in an acute care setting where you have access to resources. Care center . . . no code cart, no rapid response team, have to call 911. Few close calls, anaphylactic reactions, chest pain, acute crises.”

- “You’re in a satellite. You can’t give blood on the spot . . . a lot of things you can’t do.”

- “We have one oxygen tank, nothing on the walls. It has been stressful both for us and the patients.”

The relocation of units and staff contributed to periods of low morale, frustration, and sadness among oncology nurses. These emotions were heightened by the stress of staffing shortages because nurses were out of work with COVID-19 or under quarantine restrictions, and many non-nursing staff were working remotely, as described in the following quotes:

- “Staff in three separate areas . . . disconnected. Staffing was really difficult and staggered.”

- “We were all of a sudden not one big team but fragmented. . . . That was very difficult.”

- “Bit of a struggle with less staff . . . also members of team working remotely . . . more difficult to get in contact with them.”

Telehealth became normalized during the crisis for assessment and management of patients. Virtual telehealth, telephone assessment, and electronic messaging became essential. In addition, as part of the newly formed rapid evaluation clinic, a nurse-driven remote patient monitoring process was implemented to closely monitor patients with cancer who tested positive for COVID-19 and were recovering at home. This program was primarily staffed with inpatient nurses with limited or no previous experience in telephone triage who required intensive real-time education and support, as described in the following quotes:

- “We were inundated with phone calls from patients. With the number coming in, we weren’t able to catch up . . . didn’t have enough nurses doing phone triage.”

- “It was scary for me to triage somebody over the phone that I never laid eyes on or assessed.”

Managing Workload Intensity

The pandemic changed the work environment for oncology nursing with increased workload, extension of roles, increased telephone outreach and triage, patient screening requirements, and telehealth visits, all of which resulted in exhaustion, emotional fatigue, and distress. Hospitals were at full capacity with high-acuity patients with COVID-19, which required oncology nurses to work longer hours, float to non-oncology units, cover non-nursing responsibilities for staff working remotely, and pause vacation days because of nursing shortages, described in the following quotes:

- “I didn’t appreciate it at the beginning, but it’s a level of intensity. . . . You have to be on hyperalert. You come to work and it’s intense.”

- “I have worked more in this year than any other year of my life.”

Communication shifted based on more stringent safety guidelines, increased workload to manage telephone triage, more patient screening requirements for ambulatory visits, increased patient use of the electronic health record portal, and the need to respond to more patient and family telephone calls, which nurses described as follows:

- “Those [patient portal] messages, massive. We all feel frustrated. Our day is not done when we clock out. Overtime has increased. . . . It’s needed.”

- “We have extremely busy telephone triage. The work is spread out but still the same number of nurses.”

The approval of many non-nursing staff and oncology physician providers to work remotely contributed to oncology nurses’ increased workload intensity. Frustration at handling multiple roles and tension around patient care responsibilities were identified by the participants in ambulatory practices in the following quotes:

- “Physicians would call into patient’s room or ask the nurse, ‘How is the patient doing?’ . . . walk right past the room . . . not actually going into the patient’s room.”

- “Shifting workforce, covering clinics late, on call at night . . . was exhausting, and then covering on weekends. It is like being on a treadmill.”

- “We’re here, boots on the ground. Some providers stayed home for months . . . just unsettling.”

The intensity of the work significantly increased at the onset of the COVID-19 crisis and was sustained through its first year. The increased workload intensity led to struggles with burnout and loss of hope, which were compounded by the universal feelings of social isolation because of organizational, governmental, and community restrictions and guidelines, as participants described in the following quotes:

- “As nurses, there’s only so much we can give. I feel like there is no chance for anyone to recharge their batteries . . . drained and then you just find a way to keep going.”

- “Frustration, fatigue, emotional fatigue . . . it’s terrible.”

- “At this time [end of November 2020], everyone is truly tired, burnt out with all of this. . . . It changed our work life but also personal life. People feel isolated.”

Experiencing Emotional Distress

Oncology nurses reported emotional distress related to the care of patients and families. There were two subthemes of “Experiencing Emotional Distress:” emotional distress related to participants’ role as nurses caring for patients during the crisis, and “Mourning the Loss of Touch,” related to the nurse–patient interaction and the value of human touch. Nurses perceived patients as terrified of COVID-19, demonstrated by not wanting to come in for care and delaying care, as they described in the following quotes:

- “Terrified . . . patients are terrified.”

- “Fear, paralyzing fear. Am I going to catch this, die? I’m not going out . . . not going for my scan.”

Nurses expressed distress and perceived that patients and family members suffered because of isolation caused by restricted visitation policies. Even when visitor restrictions were relaxed by the end of the first year, there was still stress reported by the nurses. There was a sense of being without family for support that was particularly stressful for nurses caring for patients at the end of life, as described in the following quotes:

- “Telling them, ‘OK, when you leave today, you cannot come back.’ Very hard conversation. This part I’ll never forget . . . day-to-day things of patients being alone.”

- “We did [a video call] for her sister to be able to say goodbye. . . . It’s lonely. No one wants to die like that.”

- “It’s heartbreaking. . . . I think we all cry once a day. Patients are isolated, living through a pandemic, but now a pandemic with cancer.”

This distress was felt by nurses in their surrogate role in the absence of the family to provide comfort and support. Although they accepted it as part of caring for patients, there was a strong sense that they could not replace a family member’s presence, as described in the following quotes:

- “I am glad to be there with them, but I’m not the person they really want to hold them. . . . That’s frustrating.”

- “It’s really hard . . . very sad, patients are alone. They don’t have family to support them that they are used to . . . not the same. We do our best, stay with them, talk to them.”

Fear of transmission of the COVID-19 virus to family and friends was a prominent concern among oncology nurses, and it was heightened for their patients. Uncertainty and changing information about personal protective equipment, shifting safety guidelines, and emerging science about COVID-19 in the first year contributed to nurses’ emotional distress, as they described in the following quotes:

- “I was terrified if I got COVID-19, even if I was asymptomatic . . . killing one of my patients or bringing it to my home unit and infecting everyone.”

- “Not knowing if I was going to infect someone I lived with or anyone around me.”

In oncology nursing, the relationship among the nurse, patient, and family is perceived as the essence of practice, characterized by comfort, support, and human touch. “Mourning the Loss of Touch” was a subtheme of “Experiencing Emotional Distress” and was difficult for nurses, as they described in the following quotes:

- “It was hard to transition from not being able to provide a gentle touch to someone’s arm. . . . It’s our nature as nurses to try and comfort people.”

- “The human touch of oncology nursing, holding hands with a patient while getting difficult news or sitting with a patient and family . . . one of the reasons I am in oncology. It felt very strange and foreign to have to be hands-off for patient safety. . . . That’s been difficult.”

Identifying Benefits and Finding Hope

Participants were asked if there were any positive aspects or lessons learned that could be integrated into future care. The theme of “Identifying Benefits and Finding Hope” emerged, with benefits reported in the normalization of telehealth, increased use of the patient portal for communication, and new skills acquired for nurses who were reassigned in either the short or long term to other clinical settings, as they described in the following quotes:

- “I think telehealth has become an extremely viable method for patient visits . . . leveraging it for better patient care that is more convenient and accessible . . . biggest silver lining that has come from this.”

- “They are able to email their provider, which they never felt comfortable doing before. . . . They never used it [patient portal] because didn’t think it was appropriate. Now they feel closer to their provider and more accepting.”

- “It’s been awesome to learn tons of different skills, different cancers.”

Participants described their experience of hope for the vaccine, as the news of its availability emerged in February 2021, as follows:

- “Just hang in there. There is a light at the end of the tunnel with a hope that the vaccine would be released quickly and be effective.”

- “Staff are tired, but I think vaccine has given them a glimmer of hope . . . that this will hopefully come to an end.”

Discussion

Nurses during the COVID-19 crisis have been the largest group of providers in frontline care in the history of global pandemics (Paterson, Gobel, et al., 2020). Despite uncertainty, increased workload, and emotional distress, oncology nurses managed the challenges of COVID-19 as exemplified by the theme “Doing It Together: Struggling, Adapting, and Holding Each Other Up.”

The three subthemes of “Struggling With Constant Change and Uncertainty,” “Managing Workload Intensity,” and “Experiencing Emotional Distress” were integral to the experience of oncology nurses in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. The multiplicity of factors that contributed to emotional and physical fatigue were unrelenting. Although nurses described peer support as essential to coping, they also felt isolated because of changes in collegial relationships at work, such as the loss of shared lunch breaks and social isolation from their nurse colleagues outside of the workplace.

The everyday uncertainty about limited resources, unit relocations, nurse reassignments, visitation restrictions, and safety guidelines all contributed to distress (Gray et al., 2021; Ulrich et al., 2020). Concerns about skills and competencies when nurses are reassigned to alternate units have been documented and can lead to emotional and moral distress (Danielis et al., 2021; Zanville et al., 2021). The pandemic interfered with team functioning. Many non-nursing staff and physicians worked remotely, leading to decreased communication, increased job demands for nurses, and perceived lack of control (Galanis et al., 2021).

The emotional distress reported by the nurses in this study was multifactorial. The safety guidelines for visitor restriction contributed to distress for nurses who needed to provide support and act as surrogates for family, particularly for patients at the end of life (Duncan et al., 2021; Shah et al., 2021; Ulrich et al., 2020). The nurses’ concerns for patients and families were well founded, with psychosocial distress, loneliness, and adverse mental health outcomes including fear, social isolation, and existential concerns documented among patients with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic (Amaniera et al., 2021; Miaskowski et al., 2021; Nekhlyudov et al., 2020). When nurses put aside personal and emotional wellness needs to meet the needs of patients during the COVID-19 crisis, they may have compounded secondary trauma (Blackburn et al., 2020).

Telehealth was rapidly implemented for assessment, triage, interventions, and support as a means of maintaining communication and continuity of care while limiting exposure (Elkin et al., 2021; Paterson, Bacon, et al., 2020; Zon et al., 2021). APRNs primarily used video-based telehealth, which, despite some technological challenges, was a positive experience and a mode of patient care predicted to remain after the COVID-19 pandemic (Paterson, Bacon, et al., 2020). Telephone communication and messaging via the patient portal in the electronic health record were used predominantly by RNs. For ambulatory oncology practice, telephone assessment and symptom management are routine processes. However, for inpatient oncology nurses, experience with telehealth is more limited, particularly for triage. Inpatient nurses require training, communication aids, and decision-making tools for telehealth assessment and triage (Phillips et al., 2021; Steingass & Maloney-Newton, 2020). Assessment of patients with cancer is complex, and symptoms associated with cancer, cancer treatment, and COVID-19 can be similar, which led to creation of a specific assessment and triage tools for oncology nurses to provide more accurate telephone triage (Elkin et al., 2021).

The qualitative approach used in this study was highly relevant to nursing practice, providing insight into nurses’ experience and the feasibility of virtual interviews from their own perspectives (Jairath et al., 2021). However, this study involved only participants who were nurses from a single cancer center, and it required participants to recall experiences from the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Implications for Practice

The first year of the COVID-19 pandemic was the initial stage of the crisis, and it was characterized by uncertainty, increased workload, emotional and physical fatigue, fear of transmission, existential concerns among patients and families, and social isolation. Although it is unknown whether the distress reported by nurses will result in long-term psychological distress (Rattray et al., 2021) or stress-related growth (Kovner et al., 2021), it is imperative to develop strategies and support programs to assist nurses in coping with what they experienced (Ulrich et al., 2020). In the second and third years of COVID-19, there have been periods of improvement, but surges with new variants have become the new normal, and the nursing shortage is accelerating. Symptom management is a mainstay of oncology nursing practice, and new tools are needed to help distinguish the side effects of cancer therapy from COVID-19 symptoms (Elkin et al., 2021). Patients and families also experienced psychological symptom distress from the COVID-19 crisis, and oncology nurses must provide significant support and resources for patients and caregivers (Clark-Snow & Rittenberg, 2021). Constant education about the latest evidence and knowledge on COVID-19 and patients with cancer is critical for oncology nurses to be able to provide ongoing information and support (Chen et al., 2020; Clark-Snow & Rittenberg, 2021).

Telehealth has become a common tool in cancer care since the COVID-19 crisis began (Stockdill et al., 2021; Zon et al., 2021). There is a need to establish educational support programs and protocols for different types of telehealth, processes, and documentation (Steingass & Maloney-Newton, 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has been a major crisis for the delivery of oncology nursing care, but the experience has also brought to light some underlying challenges in the work environment and the need for system-level strategies to address these factors (Lyon, 2022).

The data from this study provide a foundation for a quantitative survey grounded in oncology nurses’ experiences. Based on this study’s findings, the survey should address psychological symptoms, peer support, workload, stress, and coping. Exploratory and descriptive studies remain warranted to further document the effect of the pandemic on nurses and patients in oncology practice (Zanville et al., 2021), but interventions also need to be developed and tested.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in increased workload intensity, uncertainty, disruption in teams, and physical and emotional fatigue for oncology nurses. However, the dedication and commitment to treating patients with cancer prompted a supportive peer environment to continue providing the most compassionate and highest-quality care possible across settings.

About the Authors

M. Tish Knobf, PhD, RN, FAAN, is a professor, and Youri Hwang, MSN, FNP-C, is a PhD student, both in the School of Nursing at Yale University in Orange, CT; and Catherine Sumpio, PhD, RN, is an oncology clinical nurse specialist, Lisa Barbarotta, MSN, ANP-BC, AOCNS®, is the program director of Oncology Education and Practice, and Kim Slusser, MSN, is the vice president of Patient Services, all at Smilow Cancer Hospital in New Haven, CT. No financial relationships to disclose. All authors contributed to the conceptualization and design. Knobf and Hwang completed the data collection. Hwang provided statistical support. All authors contributed to the analysis. All authors contributed to the manuscript preparation. Knobf can be reached at tish.knobf@yale.edu, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted February 2022. Accepted March 20, 2022.)

References

Amaniera, I., Bach, C., Vachani, C., Hampshire, M., Arnold-Korzeniowski, K., Healy, M., . . . Hill-Kayser, C.E. (2021). Psychosocial impact of COVID-19 pandemic on cancer patients, survivors and caregivers. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 39(3), 485–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2021.1913780

Blackburn, L., Thompson, K., Frankenfield, R., Harding, A., & Lindsey, A. (2020). The THRIVE© program: Building oncology nurse resilience through self-care strategies. Oncology Nursing Forum, 47(1), E25–E34. https://doi.org/10.1188/20.ONF.E25-E34

Cacchione, P.Z. (2020). Moral distress in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. Clinical Nursing Research, 29(4), 215–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/1054773820920385

Castelletti, S. (2020). A shift on the front line. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(23), e83. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2007028

Chen, S.-C., Lai, Y.-H., & Tsay, S.-L. (2020). Nursing perspectives on the impacts of COVID-19. Journal of Nursing Research, 28(3), e85. https://doi.org/10.1097/jnr.0000000000000389

Clark-Snow, R.A., & Rittenberg, C. (2021). Oncology nursing supportive care during the COVID-19 pandemic: Reality and challenges. Supportive Care in Cancer, 29(5), 2259–2262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-021-06005-2

Cortiula, F., Pettke, A., Bartoletti, M., Puglisi, F., & Helleday, T. (2020). Managing COVID-19 in the oncology clinic and avoiding distraction. Annals of Oncology, 31(5), 553–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annonc.2020.03.286

Creswell, J.W., & Poth, C.N. (2017). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). SAGE.

Danielis, M., Peressoni, L., Piani, T., Colaetta, T., Mesaglio, M., Mattiussi, E., & Palese, A. (2021). Nurses’ experiences of being recruited and transferred to a new sub-intensive care unit devoted to COVID-19 patients. Journal of Nursing Management, 29(5), 1149–1158. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13253

Duncan, R., Szabo, B., Jackson, Q.L., Crain, M., Lett, C., Masters, C., . . . Gullatte, M.M. (2021). Care and coping during COVID-19: Practice changes and innovations in the oncology setting. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 25(1), 48–55. https://doi.org/10.1188/21.CJON.48-55

Elkin, E., Viele, C., Schumacher, K., Boberg, M., Cunningham, M., Liu, L., & Miaskowski, C. (2021). A COVID-19 screening tool for oncology telephone triage. Supportive Care in Cancer, 29(4), 2057–2062. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05713-5

Galanis, P., Vraka, I., Fragkou, D., Bilali, A., & Kaitelidou, D. (2021). Nurse burnout and associated risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 77(8), 3286–3302. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14839

Gray, K., Dorney, P., Hoffman, L., & Crawford, A. (2021). Nurses’ pandemic lives: A mixed-methods study of experiences during COVID-19. Applied Nursing Research, 60, 151437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2021.151437

Harris, P.A., Taylor, R., Minor, B.L., Elliott, V., Fernandez, M., O’Neal, L., . . . Duda, S.N. (2019). The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 95, 103208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103208

Harris, P.A., Taylor, R., Thielke, R., Payne, J., Gonzalez, N., & Conde, J.G. (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap): A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

Indini, A., Aschele, C., Cavanna, L., Clerico, M., Daniele, B., Fiorentini, G., . . . Grossi, F. (2020). Reorganisation of medical oncology departments during novel coronavirus disease-19 pandemic: A nationwide Italian survey. European Journal of Cancer, 132, 17–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2020.03.024

Jairath, N.N., Benetato, B.B., O’Brien, S.L., & Griffen Agazio, J.B. (2021). Just-in-time qualitative research: Methodological guidelines based on the COVID-19 pandemic experience. Nursing Research, 70(3), 215–221. https://doi.org/10.1097/nnr.0000000000000504

Kovner, C., Raveis, V.H., Van Devanter, N., Yu, G., Glassman, K., & Ridge, L.J. (2021). The psychosocial impact on frontline nurses of caring for patients with COVID-19 during the first wave of the pandemic in New York City. Nursing Outlook, 69(5), 744–754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2021.03.019

Lyon, D. (2022). Advancing wellness in 2022 for professional nurses: A time for action, not gestures. Oncology Nursing Forum, 49(1), 9–10. https://doi.org/10.1188/22.ONF.9-10

Mayor, S. (2020). COVID-19: Impact on cancer workforce and delivery of care. Lancet Oncology, 21(5), 633. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(20)30240-0

Miaskowski, C., Paul, S.M., Snowberg, K., Abbott, M., Borno, H.T, Chang, S.M., . . . Van Loon, K. (2021). Loneliness and symptom burden in oncology patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cancer, 127(17), 3246–3253. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.33603

Miles, M.B., Huberman, A.M., & Saldaña, J. (2019). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (4th ed.). Sage Publishing.

Nekhlyudov, L., Duijts, S., Hudson, S.V., Jones, J.M., Keogh, J., Love, B., . . . Feuerstein, M. (2020). Addressing needs of cancer survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 14(5), 601–606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00884-w

O’Brien, B.C., Harris, I.B., Beckman, T.J., Reed, D.A., & Cook, D.A. (2014). Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine, 89(9), 1245–1251. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000000388

Oncology Nursing Society. (2022). ONS recommendations for oncology staff assignments during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.ons.org/covid-19-interim-guidelines

Pahuja, M., & Wojcikewych, D. (2020). Systems barriers to assessment and treatment of COVID-19 positive patients at the end of life. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 24(2), 302–304. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2020.0190

Parsons Leigh, J., Kemp, L.G., de Grood, C., Brundin-Mather, R., Stelfox, H.T., Ng-Kamstra, J.S., & Fiest, K.M. (2021). A qualitative study of physician perceptions and experiences of caring for critically ill patients in the context of resource strain during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Health Services Research, 21, 374. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06393-5

Paterson, C., Bacon, R., Dwyer, R., Morrison, K.S., Toohey, K., O’Dea, A., . . . Hayes, S.C. (2020). The role of telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic across the interdisciplinary cancer team: Implications for practice. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 36(6), 151090. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2020.151090

Paterson, C., Gobel, B., Gosselin, T., Haylock, P.J., Papadopoulou, C., Slusser, K., . . . Pituskin, E. (2020). Oncology nursing during a pandemic: Critical reflections in the context of COVID-19. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 36(3), 151028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2020.151028

Phillips, J., Carr, A., Guesman, K., Foreman-Lovell, M., Levesque, P., Lukas, B., . . . Grant, S. (2021). The impact of nurse-led innovations and tactics during a pandemic. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 45(3), 234–242. https://doi.org/10.1097/naq.0000000000000480

Rattray, J., McCallum, L., Hull, A., Ramsay, P., Salisbury, L., Scott, T., . . . Dixon, D. (2021). Work-related stress: The impact of COVID-19 on critical care and redeployed nurses: A mixed-methods study. BMJ Open, 11(7), e051326. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051326

Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). Sage Publishing.

Schwerdtle, P.N., Connell, C.J., Lee, S., Plummer, V., Russo, P.L., Endacott, R., & Kuhn, L. (2020). Nurse expertise: A critical resource in the COVID-19 pandemic response. Annals of Global Health, 86(1), 49. https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.2898

Shah, M., Roggenkamp, M., Ferrer, L., Burger, V., & Brassil, K.J. (2021). Mental health and COVID-19: The psychological implications of a pandemic for nurses. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 25(1), 69–75. https://doi.org/10.1188/21.CJON.69-75

Steingass, S.K., & Maloney-Newton, S. (2020). Telehealth triage and oncology nursing practice. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 36(3), 151019. https://doi.org/a0.1016/jsoncn.2020.151019

Stockdill, M.L., Barnett, M.D., Taylor, R.A., Dionne-Odom, J.N., & Bakitas, M. (2021). Telehealth in palliative care: Communication strategies from the COVID-19 pandemic. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 25(1), 17–22. https://doi.org/10.1188/21.CJON.17-22

Sullivan, R.J., Johnson, D.B., Rini, B.I., Neilan, T.G., Lovly, C.M., Moslehi, J.J., & Reynolds, K.L. (2020). COVID-19 and immune checkpoint inhibitors: Initial considerations. Journal for Immunotherapy of Cancer, 8(1), e000933. https://doi.org/10.1136/jitc-2020-000933

Thorne, S. (2016). Interpretive description: Qualitative approach for applied practice (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Thorne, S., Stephens, J., & Truant, T. (2016). Building qualitative study design using nursing’s disciplinary epistemology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(2), 451–460. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12822

Treston, C. (2020). COVID-19 in the Year of the Nurse. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 31(3), 358–360. https://doi.org/10.1097/jnc.0000000000000173

Ulrich, C.M., Rushton, C.H., & Grady, C. (2020). Nurses confronting the coronavirus: Challenges met and lessons learned to date. Nursing Outlook, 68(6), 838–844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2020.08.018

Yackzan, S., & Shah, M. (2021). Ambulatory oncology: Infrastructure development in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 25(1), 41–47. https://doi.org/10.1188/21.CJON.41-47

Zanville, N.R., Cohen, B., Gray, T.F., Phillips, C.S., Linder, L., Starkweather, A., . . . Cooley, M.E. (2021). The Oncology Nursing Society rapid review and research priorities for cancer care in the context of COVID-19. Oncology Nursing Forum, 48(2), 131–145. https://doi.org/10.1188/21.ONF.131-145

Zon, R.T., Kennedy, E.B., Adelson, K., Blau, S., Dickson, N., Gill, D., . . . Page, R.D. (2021). Telehealth in oncology: ASCO standards and practice recommendations. JCO Oncology Practice, 17(9), 546–564. https://doi.org/10.1200/op.21.00438